How Pedro Almodóvar Writes a Good “Bad” Character

Pedro Almodóvar endears film audiences with irrevocably flawed protagonists, making him the master of the good “bad” character.

So what makes a bad character good? Author and media critic Emily Nussbaum touches on this oxymoronic pop culture staple in her New Yorker piece titled “The Great Divide.” In it, she discusses the phenomenon she calls the “bad fan,” described as a viewer who doesn’t seem to understand that the deeply flawed, often violent, certainly unsavory antiheroes of some of our favorite television series are not to be rooted for.

This odd dissonance can create a “divide” among a fandom. On one side are fans who understood that All in the Family’s Archie Bunker was a willfully ignorant and ill-tempered bigot, and on the other side, fans who saw him as an every-man’s hero. Nussbaum lays out the reasoning for this dissonance, and compares Archie Bunker to more contemporary television figures, such as Breaking Bad’s Walter White.

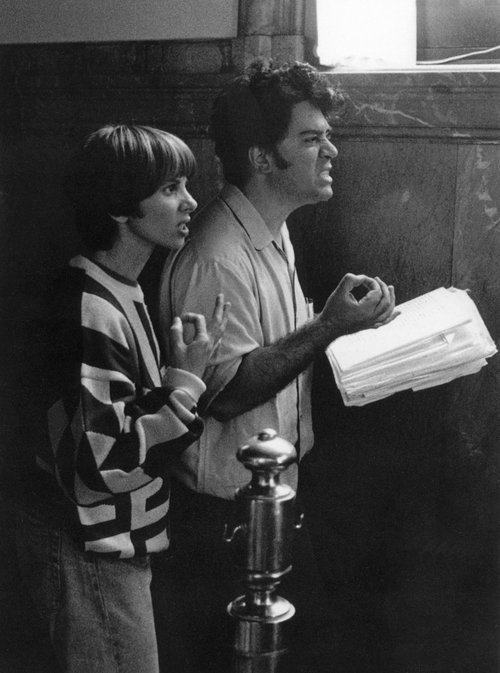

Pedro Almodóvar with actor Elena Anaya on the set of The Skin I Live In (2011). Image via Sony Pictures Classics.

Since reading this piece a few years back, the concept of the bad fan has stuck in my brain. It’s an insight that I carry with me, both as a film fan and a writer. Which brings me to one of my absolute favorite auteurs, Pedro Almodóvar. When I think of protagonists being “bad,” my mind immediately jumps to the celebrated filmmaker’s taboo-strewn filmography. His films are scandalous, depicting murder, lies, and power dynamics challenging for even the most avant-garde audience. Yet, with a little camp and empathetic finesse, Almodóvar manages to avoid falling into the trap of bad fandom.

In this post, we’ll explore Pedro Almodóvar’s masterful knack for writing great bad characters, and discuss some of the things aspiring filmmakers can glean from his approach.

Iconoclast Almodóvar

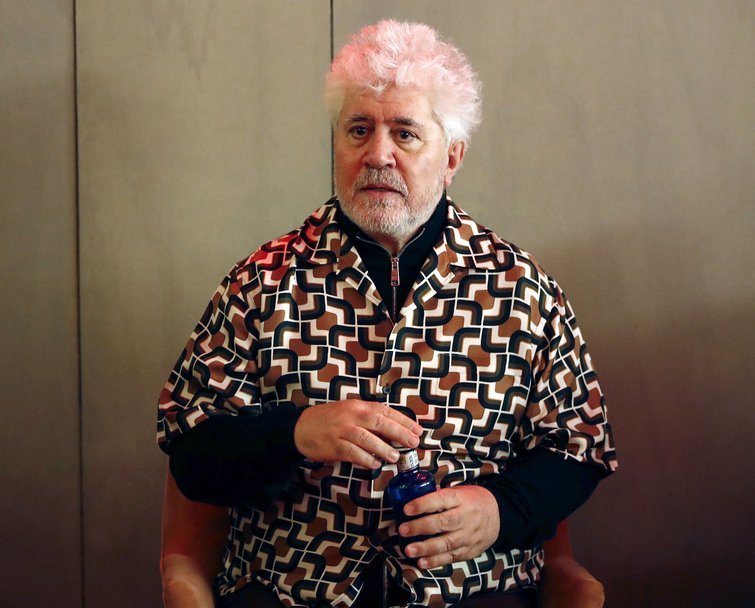

Pedro Almodovar poses during the presentation of the script of his latest film Pain and Glory in Madrid, Spain. Image via JAVIER LOPEZ/EPA-EFE/Shutterstock.

Pedro Almodóvar came of age in oppressive Francoist Spain. Therefore, his education as a filmmaker was largely self-taught. Upon Franco’s death in 1975, Almodódar found himself in the middle of a cultural renaissance, a wave of formerly repressed iconoclast film and music. Creating experimental films and performing in a satirical glam rock group, he became a central figure in the La Movida Madrileña, a movement born of the counterculture, celebrating freedom and expression.

In 1988, Pedro Almodóvar garnered international success with his feature film Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown, an artfully campy tale of criminal activity and mental pathology. Ever since, the filmmaker has dazzled fans with colorful and comedic films that endear audiences while challenging their sensibilities. With an approach centered on authenticity, he pushes the boundaries of “the character,” celebrating people who are imperfect and marginalized, coaxing us all to see the complicated realities of life we might otherwise avoid.

Bad Is Human

Victoria Abril, Miguel Bosé, and Marisa Paredes in High Heels (1991). Image via Warner Bros.

I don’t believe Almodóvar has ever depicted a character who was “evil,” but he certainly skirts the line. His 1991 film High Heels tells the story of Rebeca, a television news anchor tied up in the scandalous murder of her lover, Manuel. Early in the film, Rebeca reflects on her childhood, revealing to the audience that as a child, she knowingly killed her mother’s boyfriend, Alberto, by switching his medication. Rebeca later confesses this fact to her mother, insisting that she only did it out of a deep love for her mother, believing that she was somehow setting her free.

Although Rebeca has murdered (at least once), her deep love for her mother, and marked impulsivity, imbue her crime with humanity. Rebeca’s impulsive nature drives the film, leaving a wake of lies and secrets as she fumbles her way through the ramifications of her actions. Since the film’s conflict stems entirely from Rebeca’s crimes, the audience cannot simply point to a worse “evil-doer” in the story. Rebeca is, in fact, the story’s “bad guy.” Therefore, the audience must grapple honestly and critically with the protagonist’s moral impairment.

Antonio Banderas and Victoria Abril in Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down! (1989). Image via HBO Max.

In Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down! (1989), Almodóvar endears us to Ricky, a mentally unstable kidnapper who manages to woo his hostage Marina, a former adult film star, into falling in love with him. Who could have imagined that Stockholm syndrome could so masterfully thread the plot of a romantic comedy? As unsettling as it may seem at the outset, Almodóvar somehow makes it work. A closer look at Ricky’s past provides more complex layers to his cast of mind and his view of love and possession.

By imbuing misdeed with humanity, he opens our hearts to those who have perpetrated even the most heinous crimes. Almodóvar reveals the complexity of both our best and worst human selves, providing context for people’s inevitable transgressions, and lending grace to those far-fallen.

People at the Margins

One consistent hallmark of Almodóvar’s work is his ability to humanize those at the margins, people who were seldom afforded an empathetic lens. In his 1999 drama All About My Mother, he effortlessly casts a loving light on those typically depicted in tortured caricature, including people in sex work, people struggling with addiction and dealing drugs, people battling HIV and AIDS. Rather than relegating his most resilient and interesting characters to token suffering, he shows them partaking in tender and loving friendships, acknowledging their hardship but never exploiting it.

Cecilia Roth and Eloy Azorin in All About My Mother (1999). Image via Sony Pictures Classics.

Naturally, being at the margins never makes someone inherently bad. However, hardship often begets desperation. Many of these characters recount their worst moments, confessing their crimes, their lies, their unsavory past deeds. By building an authentic world, one with moral complexity and misfortune, he provides context for his character’s trespasses. Manuela hides the truth about Esteban’s father, not to hurt him but to protect him. When we find that Lola, the transgender woman who is in fact Esteban’s biological father, has given Rosa HIV, we do not hate Lola, but rather understand her complexities.

Also laying at the heart of Pedro Almodóvar’s body of work is the spirit of counterculture. Just as he depicts people at the margins, he also reveals the atypical world they occupy. By flouting societal norms, the filmmaker can “reset” the moral bounds, allowing the audience to discard propriety and measure a character by the substance of their heart and the reality of their circumstances. In an Almodóvar film, a character’s misdeeds are intrinsically tied to their circumstances. He doesn’t apologize for his characters, but he will show you how they got to where they are.

Three Quick Tips for Writing a Good Bad Character

So, what makes these imperfect characters so great to watch? Here are some guides to writing a good “bad” character.

1. Confession

Allow your character to confess their crime, in their own words. One great way to avoid any confusion about your protagonist’s moral standing is to make them say it out loud. This will confront your audience with the cold, hard truth, and create an authentic line of tension for your story. Who needs a bad guy when your hero is their own worst enemy?

2. Heart

Allow your character to care deeply for something. Even if their passion is somehow misguided, it’ll reveal their heart to the audience. It’s easy to manifest a villain because they are flatly evil, and one need not reveal that villain’s sense of fear or love to make a story work. However, showing the heart of your imperfect hero will go a long way to cultivate empathy.

3. Consequence

Confront your character with the consequences of their deeds. They may get away with their crimes in the carceral sense, but they must not be allowed to come out unscathed. Whether your hero holds firmly to denial or experiences watershed catharsis, they must (at the end of the day) lay in the bed they’ve made.

Almodóvar 2020

To this day, Pedro Almodóvar continues to delight audiences with his playful, yet challenging, films. Just this year, he’s premiered his short film “The Human Voice,” a collaboration with renowned actor Tilda Swinton and adapted from the Jean Cocteau play of the same name. Shot over the summer at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, it was an outlier in an industry that had largely ground to a halt. The film is also the filmmaker’s English language debut and has enjoyed quite a positive reception.

If you’ve yet to acquaint yourself with the work of Pedro Almodóvar, then it’s high time you did. Having written and directed twenty-two feature films and a handful of short films, this prolific auteur’s filmography provides plenty for passionate cinephiles to sink their teeth into.

Cover image via El Deseo S A/Kobal/Shutterstock.