Screenwriter Norman Steinberg on Mel Brooks, Richard Pryor, and Getting Heard

Norman Steinberg has worked on some of your favorite projects with some of your favorite people. We sat down with him recently to talk some shop.

Recently, we spoke with Norman Steinberg from his idyllic home in upstate New York. It was hard not to think of one of his classic comedic films as he continually moved from room to room to avoid the blaring sound of the gardener’s leaf blower. He interrupted every anecdote with “Can you believe this guy?” as the roar of the blower would creep closer.

At nearly 80, Steinberg isn’t slowing down. He’s currently writing the book for a musical based on the 18th-century comedy of manners The School for Scandal with composer Charlie Fox (who wrote the theme songs to all your favorite ’70s shows, including Happy Days, Laverne and Shirley, and Monday Night Football), he quipped, “You can’t make a living in the theater, but you can make a killing.”

PremiumBeat: It’s hard not to imagine the writing process of Blazing Saddles as a combination of a Dean Martin roast and a comedy brawl version of Fight Club. How were you able to get your ideas heard and implemented among such giant personalities as Mel Brooks and Richard Pryor?

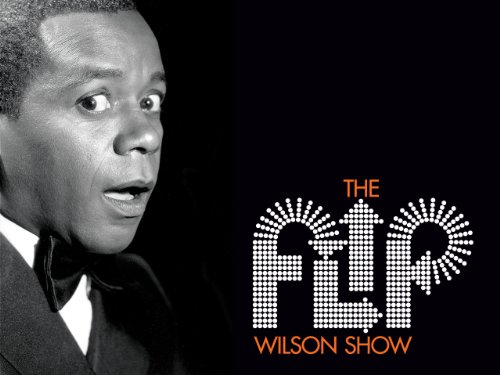

Norman Steinberg: By speaking up, by not being afraid. Basically when we started, it was me and Andrew Bergman, and I brought along Alan Uger, who left after a couple of weeks and still got credit for some reason — and Mel. Mel says I’m looking around the room, and I see four Jews — we need a person of color. Who can we get? I did the Flip Wilson show, and Flip went to number one, and we had all these great guest stars — Bing Crosby, Jack Benny. I had worked with Richard Pryor on the Flip Wilson show. My writing partner was George Carlin. I brought Richie in. I told him, “Hey, we are doing this film, and it’s about a black sheriff in the old west,” and he kinda lost his breath. “Mel Brooks? Mel Brooks?” He was a huge fan of Mel’s. I told him we’d love for him to write with us. He said, “Get me some money, get me train fare, get me a hotel, and I’ll be there.”

First day, he came in late. We started at ten; he got there at twelve. “CPT” he said. He sat down, and we started explaining the story, where we were, and he was going “ah ha ah ha” — pulls out a little vial. I didn’t even know what it was, and it was coke. Started doing coke. He turns to Mel, gestures to it and says “Brother Mel?” Mel says “Me? Never before lunch.” And we started.

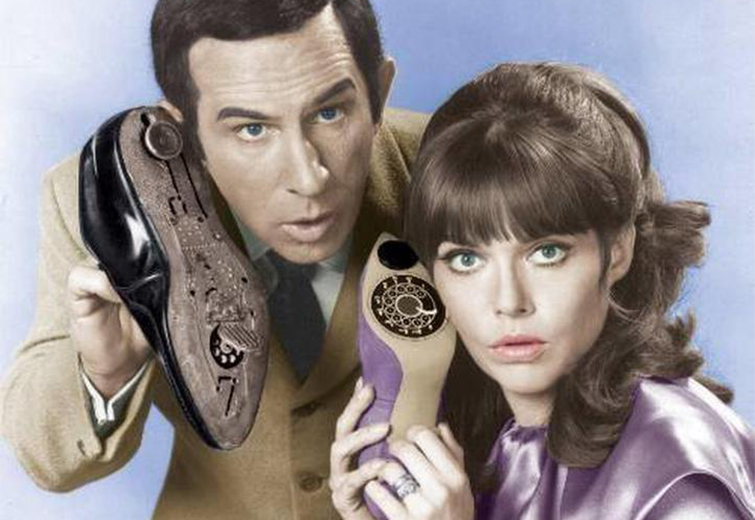

To be in the room with these two guys. Incredible. Mel Brooks was my hero. He helped me start my career by hooking me up with the producer of Get Smart. Mel called and told me you want to be a writer (I was a lawyer) write a spec script, and I did. I sent that script to Leonard Stern at Get Smart, and a week later he called [to say] that it’s a good script. “If the show gets picked up, we’ll buy it.” The show got cancelled. I quit my job anyway and started being a writer.

I wrote for Cash Box (trade music magazine), then I got an agent through someone I met through the army reserves — happened to be Bill Cosby’s agent. He got me a job writing on I Am The President, David Frye’s comedy album about Lyndon Johnson leaving the white house. David Frye — one of the great impressionists (“not a painter”) He was crazy, but he could do anyone. I think I got five hundred dollars and royalties. It was a hit. Kept going up the charts. The album won a Grammy.

Next I did Comedy Tonight on CBS — star was Robert Klein and Madeline Kahn and Peter Boyle and all the great second city players. We did ten shows, was thrilling writing the sketches. It was a real writers room — Tom Meehan (Annie, The Producers) — Just a great group of people.

Then I go out to California to do Frye’s next album, Radio Free Nixon — all happenstance — I run into Robert Klein, and he’s doing a new show with Flip Wilson — says I should come by, and I go out to see him and meet Herb Baker. They were looking for a new writer and offered me seven hundred and fifty a week, which was a fortune to me. Flip paired me with George Carlin — he was great, and he became my partner. It was a number one show — we get nominated for an Emmy, so I get an Emmy! My first two jobs basically, I get a Grammy and an Emmy (handed to me by Jimmy Durante.)

I was then offered $1,500 a week, and I quit because I wanted to come back to NY. Gary Belkin hired me to do a special, Aquacade in Acapulco, with Tony Randall, Ed McMahon, Aquamantics, Stiller and Meara and Mel. This was a couple of years later. The only other time I saw Mel was at the unemployment office. We wrote a sketch together — I was in the sketch. Wonderful, I had no fear of saying what was on my mind and what I thought was funny, and I could make him laugh. Mel is tough as hell, and he yells at people, and I would say “Shut the fuck up.” Getting heard — you just rolled the dice. It’s the same thing in the writers room — you have to learn to take a punch. That was my indoctrination under fire. That was my instinct — I’m going for it. With Richard and Mel, it was like watching these two masters just go for it. They so respected each other and just laugh and embellished each other. I could never duplicate that experience — it was incredible. If you go at Mel — he will stand his ground, but he will respect you.

This is how it works with Mel. He doesn’t sit down and write a script. He pitches — he says things off the top of his head. Like once we were having dinner and he said “Whoa that’s hot! My tongue just dialed the fire department.” He is the funniest man I know.

The day that Mel showed the film to Warner Bros. — he came back to the office, he was ashen. He said they didn’t laugh once. He said “I’m going to re-cut the film.” Andy and I begged him to wait until the screening we had that night with all the Warner office workers. And they went bat shit, and it never changed. People were falling on the floor — because it was so outrageous at the time. And Mel said “Fuck ’em this is our film,” and that was the film that was released.

PB: You’ve been involved in a lot of projects that speak to social justice — Blazing Saddles tackled race in its own zany way, and Free To Be You and Me dealt with gender identity and gender roles way before there were national conversations on which bathroom you can use or who should be able to serve in the military. How did you come to that project, and what was the process creating that show with so many liberal icons like Marlo Thomas and Alan Alda?

NS: Free To Be You and Me was created by Carol and Bruce Hart with Marlo — they did the album, then we did the TV Special (also an Emmy winner!). I was working with Carol and Bruce on something, and they asked me if I could help them. Marlo was great. I brought Mel into it, and Mel and Marlo did the baby song. It was great — puppets by Waylon Flowers — he was a genius. Marlo is a great producer and a really good person.

PB: You have bounced often between features and TV work — does one have more of an appeal to you than the other?

NS: Most of my career was in film — when I started, you either were film or TV and never the twain, but after Blazing Saddles, I was doing piecemeal here or there. I pitched some movies and sold one to Fox. Producer Bud Austin just adored Blazing Saddles and asked if I would consider heading up comedy development for Paramount TV and promised that anything I wrote on the side was a separate deal. I had this crazy Robin Hood idea, When Things Were Rotten, and sold it to ABC and brought Mel in. I had to give up my writing credit because of the Paramount job. So, I worked in TV, but I was really disdainful of it. It was a step down at that time. Now it’s everything.

PB: My Favorite Year. Just mentioning the title of that film brings a smile to my face. How did that come about?

NS: Dennis Palumbo wrote a script about Wyatt Earp, who comes to New York to publish a book — this guy is a drunk and he has a gun. The book publisher sends a young man to babysit him. The producers said it’s period, expensive — we’ll never get it made — how about the same kind of relationship, but between Errol Flynn and Mel Brooks? Mel got in involved. The script became, In like Flynn. Mel hated the script and gave Dennis notes. He refused the notes, so Mel called me that he was looking for someone to rewrite it. I said I’d do it. Mel said “I can’t pay you enough.” I said “Can’t or won’t?” Ten drafts and four years later, we got it made.

Tom Hanks was first in the door, but the director, Richard Benjamin, thought he was too sketchy. Mark Linn-Baker was great. But who knows how Tom Hanks would have been. He ended up doing Splash instead. Getting Peter O’Toole was like a dream come true. We said we wanted Peter O’Toole. MGM said “He’s a drunk, get someone else.” We said, “He’s perfect, and he doesn’t drink anymore.” We did meet with Albert Finney. He had just finished Shoot the Moon and Annie back to back. He told us he needed six months to rest. We knew we couldn’t wait — there could be a whole new batch of executives then, and our movie could be shelved. We told him we couldn’t wait. Finney said to us “O’Toole’s your man — I went to RADA with him. He’s your guy. I know I’m going to regret this. I said this once before and that was Lawrence of Arabia.”

Cover image via Warner Bros.

Looking for more industry interviews? Check these out.

- Actor Charlie Schlatter on Work, Health, and Complacency

- Interview: How Filmmaker Jessica Sanders Brought a Tiny Person into a Big World

- Interview: Women Texas Film Festival founder, Justina Walford

- Interview: Filmmaker Bradley Olsen and His FCPX Documentary “Off the Tracks”

- Best F[r]iends: Greg Sestero on Making Movies With Tommy Wiseau