Video Editing Tips and Tricks from Oscar-Nominated Editor Joe Walker

Learn useful editing tips and tricks from Arrival and Sicario editor Joe Walker

No matter how long you’ve been editing, and no matter what kind of material you work with, you can always learn useful tips and tricks from leaders in the industry.

While working on this post on the making of Arrival, I listened to and read a lot of articles featuring the film’s editor, Joe Walker. Not only did his work on the film earn him a second Oscar nomination (the first for 12 Years A Slave), but he’s also been very generous in sharing his expertise.

Joe is currently in post-production for the highly anticipated Blade Runner 2049.

Interestingly, Joe likes to get involved in the editing of the teaser trailers, as this helps him repurpose the same material in a much more compact form, which can inspire him to be bolder with the actual film.

In this post, I’ll cover several of the practical editing tips that Joe has shared that can improve how you edit.

Improve Your Editing with Tips from Joe Walker

Most of the tips from Joe in this post are from two excellent sources. The first is an absolutely must-read article, written by Joe himself, and published in MovieMaker magazine.

The second is this engaging interview with DP/30 (above), which offers a “super-sized” chat with Joe about his work on Arrival, Sicario, and even a little bit on BladeRunner 2049.

Since Joe was nominated for an Oscar and Arrival has been so well-received, it’s highly likely that he’s also shared many of these same points in other interviews, too.

Structure Your Edit

In the DP/30 interview, Joe mentions a new technique that he’s developed — he tries to edit backwards.

By this, he means that when he’s first constructing a scene, he tries to work backward from the one line, key shot, or moment that the scene is really all about — something he needs to “land” to make the edit work.

So rather than starting with the opening shot and working toward that moment (which sometimes doesn’t pan out), he starts from the end and works backwards, structuring the shot sizes, cutting, and timing to make that core moment really shines.

Joe attributes this to learning to edit film during his days at the BBC, hand-splicing every cut, and the discipline it required to think through your edit before you even began chopping up the rushes.

These days, it’s easy to slap everything down on the timeline and skim through rushes. Learning to stop and think through a scene, consider what it’s really about, and determine its key moments can take practice, but the end result is worth it.

Another tip that Joe has shared in several interviews arose from Arrival‘s dream sequences. They needed to condense several scenes into one and remove a distracting story thread, all while keeping a key piece of information in the film. How did Joe solve this problem?

As an experiment, we very crudely strung together only the pieces we needed, at one point creating a really jarring join between one line of Ian’s and another.

This jarring cut was left in, along with a bunch of other tricks you can read about in the MovieMaker magazine article, but it reveals an important technique for any edit, which is to start with only the pieces you need.

So often, the work of inexperienced editors is overly long because they start with everything and (sometimes) try to whittle it down instead of selecting only essential material and finding creative ways of making it work.

If you’ve stopped to think through the scene and its core beats, these should be the elements you’re starting with and working backward from.

Playing with Time

The editor’s greatest superpower is playing with time: speeding things up or slowing them down to examine a moment in microscopic detail … “Pace” isn’t just rattling through a film without allowing anyone to feel anything; you have to add variety and landscape to the moments you want to dwell on. A director I worked with used to say, “You’ve got to sell some to buy others.” Apply firm scrutiny of the sense of time throughout the story.

In many ways, Joe’s tip about working on the effective pacing and sense of time in each scene is a macro version of the tip about cutting a scene backwards. To get the film to work as a whole, you need to have moments of both tension and release — moments to absorb what’s happened and moments to rush along without all the answers.

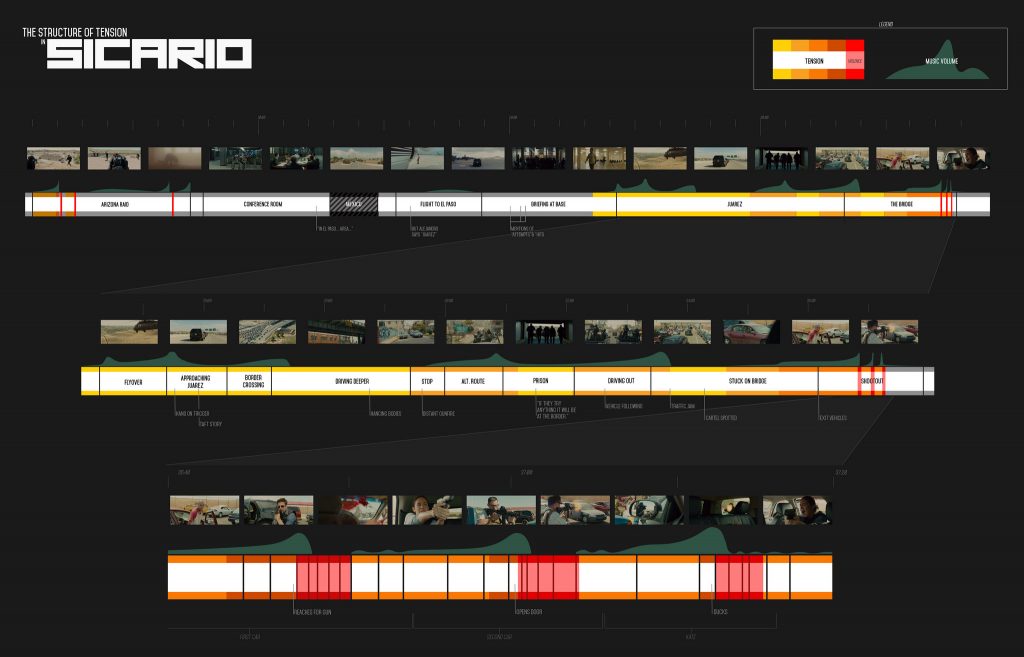

There is a brilliant breakdown of how this plays out in Sicario from CineFix, which is well worth a watch for a more detailed look at this concept.

Not Cutting Is Better

I had this brilliant mentor and taught me the value of not cutting. And that’s the biggest impact of cutting with film on me … He used to say “Just because they shot it, you don’t have to use it.”

In the DP/30 interview Joe talks about something he learned from a film editing mentor on the power of not cutting. He describes spending all afternoon cutting between a wide shot and three close-ups, trying to milk each of the close-ups for all the best bits of each performance while keeping up with the fast-paced dialogue.

After seeing Walker’s work, the senior editor asked him to see the wide shot that featured all of the best performances, body language, and looks. His conclusion was, “It’s better.”

If you have great performances to work with, not cutting is many times more powerful than trying to accentuate a moment with a close up. Often, the audience is editing a wide shot in their heads anyway, as they shift their focus from character to character.

Image from MovieMaker.com

The Sound of Silence

I come from a music background, I was a composer and I’m very nervous about over-reliance on temp tracks. I think they are unfair to composers because they tie their hands behind their backs before they’ve had a chance to respond to a tabula rasa, and also it means in sound terms, it prohibits the investigation of silence and the investigation of sound effects, so I like, if possible, to do things with an atmosphere or a mood, or in Twelve Years a Slave, cicadas, for example.

In this interview from Gordon Burkell of AOTG.com, Joe talks about avoiding an over-reliance on editing with temp tracks — he likes to keep them off for as long as possible. This is a tried-and-true technique for many experienced editors, but it takes real discipline to watch scenes “dry.”

It feels more satisfying to slap on some temp music, cut to its rhythm, and get the instant gratification that it all “works.” It also then feels painful to undo anything that works to that track because, you know, ”it’s working.” This is the inherent problem with temp tracks. They are temporary.

You will get far better results by keeping the music off for as long as possible, ensuring that the scene can “stand up and carry itself” on it’s own. Then, when the (preferably composed) music comes into the cut, the scene will really shine.

As a related tip (and something that Walter Murch is also known for), Joe will edit with the speakers completely turned off, to see if the scene works without any dialogue.

We both love cutting with the speakers off, which is just something we started doing on Sicario, and cutting it as a silent movie sometimes … but it seems to be a good approach with [Villeneuve’s] films, that if it works with just the visuals and you can tell what’s going on and the story is working … it makes you very tough [on the story].

These are just “some” of the tips and tricks that Joe has shared in his interviews, so I’d encourage you to read and watch as much as you can about his work.

Do you know editing tips from other industry leaders? Share in the comments.