Filmmaking with the Greats: Production Problem-solving

Filmmaking is problem-solving. The tools of the trade aren’t molds into which we cram the stuff of filmmaking. They’re the tools we use to try to tame the wild and unruly beasts that we call movies. In almost every production, there comes a moment when you need to get creative. Maybe it’s a weird shot, or some strange lighting, but you have to look at what you have and figure out how to get the square peg into the round hole. Solutions can be crude, elegant, or outright insane, but they can become the stuff of filmmaking legend when they work.

In this round-up, we look at four wildly different movies from The Vault of Great Films to see how both beloved and infamous scenes came together despite their production challenges.

Aliens

James Cameron‘s storied sequel to Alien is a thing of Hollywood legend. It was underfunded (with Cameron and his wife and producer Gale Anne Hurd on the hook personally for any overages), there were several clashes between Cameron and the British film crew at Pinewood Studios, and it was overly ambitious for the young director.

Despite the challenges, however, Aliens went on to critical acclaim and was one of the highest-grossing films of 1986, cementing Cameron’s career. But, production wasn’t a cakewalk for the former art director. The creature effects alone were groundbreaking, but one standout production challenge was the rigs for the intelligent guns.

These beauties were constructed from German MG 42 machine guns, Steadicams, and motorcycle parts. Each one weighed between 65-70 pounds, but it had to look seamless when Private Vasquez (Jennette Goldstein) and Private Drake (Mark Rolston) wielded these bulky weapons.

So what was the solution?

Gaffer’s tape. Lots of it. Goldstein and Rolston had the harnesses taped to their torsos to keep the awkward rigs from falling off. So much tape, in fact, that needing to go to the bathroom was . . . discouraged.

With a history of such antics as using styrofoam takeout boxes as set design in Battle Beyond the Stars, Cameron had already proven himself a frugal-but-innovative problem-solver on set. The takeaway: when in doubt, don’t over-complicate things. Use tape. Lots of it.

Ghostbusters

When Dan Aykroyd first began writing what would become one of the most beloved comedies of the ’80s, he didn’t just land on ghosts on a whim. His family had a long tradition of the occult and the arcane. An avowed Spiritualist, Akyroyd (and other members of his family) believe that “[spirits] are between here and there, that they exist between the fourth and fifth dimensions, and that they visit us frequently” (Psychic News, 2009). Aykroyd’s father, Peter Aykroyd Sr., authored A History of Ghosts (2009), which detailed the Aykroyd family’s historical involvement in Spiritualism. And Aykroyd’s great-grandfather was a dentist and a mystic who corresponded with Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

So, Aykroyd had a thing for ghosts. The earliest drafts of the film had himself, John Belushi, and Eddie Murphy in the roles of the ghostbusters (but the realities of production and life would change all that). There were several hurdles and speedbumps on the way to production for Ghostbusters, but the project really came to life when Ivan Reitman, known at the time for directing this gem, came on board. The two comics retired to a cabin for a couple of weeks, hammered out the script, and got a green light for the sturdy production budget of $25 million (it would go on to earn $300 million).

Ghostbusters was unique at the time. It was a comedy filled with special effects, which was unheard of. Coca Cola owned Columbia, and they thought the combination was so absurd they threatened to kill the production. But Boss Film Studios saved the day. This brand-new effects house was full of talent fleeing the increasingly corporatized Industrial Light and Magic. So, packed with genius effects artists, Ghostbusters pulled off its ambitious script in just ten months.

So, what production innovations helped this little-movie-that-could standout? There were many, but our favorite is Slimer. This cheery little gourmand required a team of puppeteers to wiggle his face about, and he was worn as a hat by his primary puppeteer. That’s a lot of people for one ghost, which meant he couldn’t move around. No problem, the puppeteers were keyed out later, but Slimer is mostly zooming around the film, coming right at the audience with his maw agape or floating off down a hallway to annoy the ghostbusters. So, how did Reitman and his gang film this?

They moved the camera. Instead of zooming everybody’s favorite green ghost around, cinematographer László Kovács and his team zoomed the entire camera back and forth to reverse-engineer the movements they needed for the little ghost.

So, when the realities of shooting something impossible present themselves, take a page from Ghostbusters. Make it possible.

The Exorcist

There are some who believe this film was cursed — and for good reason. It is still one of the best horror films of all time, and the marketing behind its initial release was nothing short of brilliant. There were claims that ambulances were stationed outside the theaters for viewers who suffered health issues from watching. There were claims that simply airing the film in your theater was inviting demonic possession of the theater itself. And it didn’t hurt that William Peter Blatty had done his research. Pazuzu — the demon who possesses Regan in the film — was, indeed, a demon from what is now modern-day Iraq, and the film opens with this factual excavation. Even the pope claimed that demonology was a valid and essential branch of Catholic doctrine — and that it shouldn’t simply be left alone in dark corners.

That’s a lot. But then there were the real-world production issues that also plagued the film. Multiple cast and crew members suffered deaths in the family during filming. Then a fire broke out, damaging a great deal of the set, but the room used as Regan’s (the possessed girl) was completely untouched. And if that weren’t enough, the film captures an actual murderer, in Paul Bateson, who appears as a radiological assistant. Things got so tense during production that an actual Catholic priest blessed the film to try to calm the crew. (This blessing came from none other than Father Thomas Bermingham, the film’s technical advisor. Director William Friedkin wanted Bermingham to perform an actual exorcism on the production, but the good father feared that might just agitate the crew even more.)

After the film came out, the reception was so visceral that Linda Blair had to be placed under the protection of bodyguards because some viewers believed she was actually evil incarnate. If that doesn’t tell you how badly this film scared everybody, then you might just be possessed yourself.

But before this infamous film found its way to horrified viewers, the crew had to overcome some production challenges — as you do. However, any showcase of legendary production tricks wouldn’t be complete if it didn’t point out some epic failures.

In one of the film’s famous scenes, Regan, possessed at this point by Pazuzu, is flailing about on her bed, hingeing upright and then flat over and over faster than humanly possible and stiff as a board. It’s a truly horrifying effect, and the crew accomplished it by lacing a brace board to Blair’s back. Unfortunately for the young actress, however, some of the lacing came loose. The cries of agony you hear during this scene are real. Being whipped about like that with the board improperly laced to her back actually fractured Blair’s spine.

But, The Exorcist wasn’t finished punishing its cast. In another scene, Regan slaps her mother, played by Ellen Burstyn, across the room. In order to exaggerate the effect of the slap, a cable was affixed to Burstyn, and members of the cast yanked her across the floor. Well, they yanked too hard, slamming Burstyn’s head against the wall. Again, the cries of agony you see in the film are real — the take that captured what would be a permanent injury is the one that made the final cut.

So, it goes without saying that when making any movie — much less one that’s inviting the Forces of Darkness to the party — the safety of the cast and crew always comes first. Triple-check everything. Do you want to be the one who didn’t tie the board correctly and snapped a little girl’s spine? Yeah, didn’t think so.

Flight of the Navigator (1986) is a bona fide cult classic. It has Disney fans, and it has science fiction fans, and they come together with their love for this sci-fi charmer. Known for its iconic space ship, the Trimaxion Drone Ship, and its robotic commander, “Max” (Paul Reubens), Flight of the Navigator was, for many, their first encounter with the idea of time dilation, which would go on to be a major trope in science fiction cinema.

There were several firsts involved with this film. It was the first film to feature an entirely electronically created soundtrack, composed and performed by Alan Silvestri using the Synclavier. It was also one of the first Hollywood films to make significant use of CGI effects. While there were two full-size versions of the ship on the production, the film was the first to use image-based lighting and morphing to bring those practical set pieces fully to life. Director Randal Kleiser‘s brother, Jeff Kleiser, used reflection mapping to simulate the ship’s chrome surface — another industry first. (The idea came from commercial work in this vein that Jeff had done for Tide in 1985.)

The definitive superfan of Flight of the Navigator has to be Captain Disillusion, whose 2021 video uncovers a treasure trove of details about the film’s production. I highly recommend you watch the entire thing, but it’s 41 minutes long. So, for our production showcase here, let’s extract a few of the details that make this movie one of the production problem-solving greats.

We’ll leave the innovations behind the film’s CGI to Captain Disillusion and the video, but for us, the real creativity comes down to the practical effects involved with the spaceship. There were two life-sized versions of the ship, built from a fiberglass mold in California and shipped to the shooting location in Florida. One of these two ships was solid (the lightweight version of the two), and the other was hollow, allowing our hero, David Freeman (Joey Cramer), to hang out the open door and climb in and out of the aluminum-dressed interior. The primary reason why they built the two “real” ships was, well . . . realism. The actors could actually touch the ships. But this created a production challenge: how do you make the ships float?

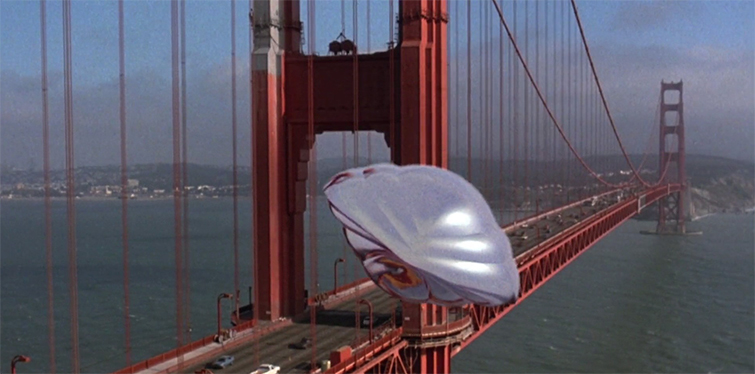

The answer is some clever cinematography. The lightweight ship could be suspended by a single wire, which we see mostly when it’s still trapped in the hangar (if you look close, you can see it). The heavier ship had a load-bearing pole and could be attached to lifts and cranes. With the correct camera angle (or some clever blocking), we never saw the supporting apparatus and bought the illusion that the ship was floating. You can see how the filmmakers did it by looking at the following two images. First, the end result . . .

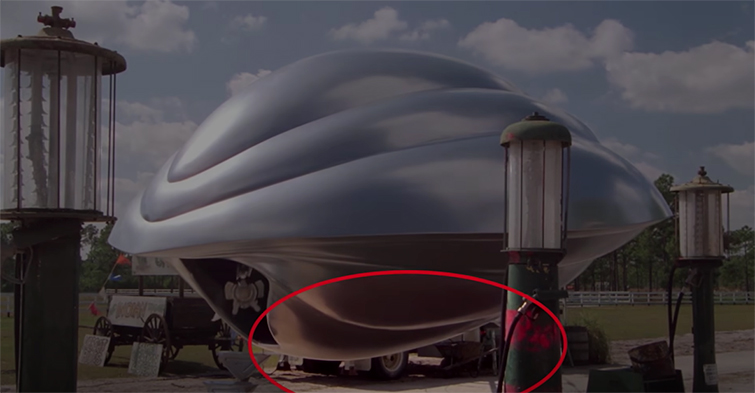

. . . and then a second image capturing the ship’s support in action . . .

By using the curvature of the hill, and the curvature of the ship’s belly, the filmmakers were able to hide the bulk of the machine just out of sight. You don’t need that much sky to make it look like something’s hovering. You need just enough to pull off the illusion.

And when you couldn’t use this trick, you built on what you’d already sold us. The ship floats, so why would we think that a practical vehicle in the background would have anything to do with the ship? We can see that bit of sleight of hand in action in this shot . . .

These magnificent ships would later end up in a Disney backlot, and then they would be repurposed for other props, but they are still icons of creative filmmaking at a time when CGI was still only capable of polygons and primary colors.

And there you have it. Production secrets from the pros. We don’t necessarily recommend you recreate all of these on your next shoot, but if you can draw some inspiration, go forth and innovate. Just, take care of your cast and crew, please . . .

Cover image via Columbia Pictures.

For more on filmmaking, check out these articles: