How to Build a Starship — A Filmmaker’s Guide

Starships are dynamic set pieces in science fiction filmmaking, but they require a bit of forethought to design. Here’s what you should consider.

In the 1950s, advances in lens technology and film stock changed how viewers experienced movies. Lenses like CinemaScope and film stock like VistaVision brought dramatically wider and larger images to theater audiences. It was a watershed moment for filmmaking, and nowhere were its effects more breathtaking than in Western films.

Wait, Westerns?

The expansive landscapes of the “American West” were so jolting in their strange largeness that, for many, they felt alien. Not of this world. These landscapes performed in film-like characters themselves, capable of providing shelter or exacting revenge — or even simply making people disappear. They didn’t follow the rules of men, and they were more than merely inert features of the land.

A similar living strangeness arose from the inanimate in science fiction films — starships. These Goliath vessels lumber effortlessly through the cosmos. They’re stoic, implacable, and very much alive. They give their crews the breath of life; they hold them while they sleep; and their mechanical hearts keep their many parts moving, fighting, and exploring. They can give life, and they can take it away. They can be temperamental or nurturing or even downright evil.

In a science fiction film, the starship is more than just a location. It has an immediate effect on the lives and relationships of the crew that operates it. How they live, how they love, and even how they die are all subject to the operation of their ship. The relationship between a ship and its crew is almost parental, and what happens to the ship determines what happens to the story in the film.

Starship design, however, is more than just some rocket engines and blinking lights. There are functional ideas and design aesthetics behind all of your favorite onscreen starships. So let’s take a look at what we know about starships and how some of the most famous came to be.

What’s in a Starship?

So what are the rules behind starship design?

There aren’t any.

Every ship you’ve ever fallen in love with on the screen was the result of a different designer’s inspiration — we’ll take a look at a few later on. Starships usually make their appearances within the science fiction genre, but there isn’t just one “science fiction.” Every science fiction film is a new “science fiction,” and each establishes its own rules of operation. That means different ships have been designed to different levels of detail and operation.

In Star Trek, for example, if your inertial dampeners aren’t functioning properly, the minute you go to warp, you will flatten all of your crew into fleshy pancakes. In Star Wars, though, you don’t hear much about them or why they’re even necessary. Different science fictions, different degrees of technical detail.

So, you have some latitude, generally speaking, when it comes to the sophistication of your ship design. There are a few conventions, however, that you might find helpful — there’s no reason to reinvent the scientific wheel every time you want to tell a story in space. First, propulsion . . .

Propulsion Design

The scope of your story will dictate how you approach propulsion. If, for example, your story spans the galaxy (or more), you have to incorporate some form of faster-than-light (FTL) travel. In Star Wars, it’s the “hyperdrive,” in Star Trek, it’s “warp speed,” and in Dune . . . well . . . um, psychic navigators use a magic spice called melange to predict the future and operate the “fold space drive.”

As we said, there’s no one science fiction. Different strokes for different folks.

But back to propulsion: if your story is contained to a more realistic scope, like the solar system in The Expanse, then you don’t need to be able to fold space and time — you just need very efficient engines that can get you around in a reasonable amount of time.

At present, for example, using our best technology, it would take us a blazing-fast seven months to get to Mars. If you want to do anything at all in your starship story other than just go to one destination, once, you’re going to need to be able to move around faster than that.

Fuel

But that doesn’t mean you have to be able to explain all of the details. Returning to The Expanse, the ships in this series rely on a fusion drive called the Epstein Drive, which consumes fuel pellets to create thrust. Asked exactly how these engines operate, the show’s creators responded with “Very well. Efficiently.” They’re fast, and that, as they say, is good enough for rock ‘n roll.

Whichever scope you go with, you’re going to need some form of sub-warp engines (even if you don’t also need warp engines). You can’t very well warp from Earth’s orbit to the moon’s, for example. It’s too close. That means you’ll need fuel, which is a good thing. A finite fuel supply can create a sense of urgency in your story. You could run out it, and, well . . . that would be a problem in the infinite darkness of space.

Gravity

Whether or not the occupants of your ship are subject to the laws of artificial gravity generally depends on the “realness” of your movie. Returning to The Expanse, which positions itself as pretty real, there isn’t any because, as far as science can tell, there is no way to generate artificial gravity except by creating inertial force by spinning the surface you want to stand on. Instead, the crew of the Rocinante in The Expanse rely on magnetic boots.

In many other science fiction films, artificial gravity is just a thing that doesn’t need explaining. Sometimes it goes haywire, and everybody starts floating (actually, this happens pretty often — the pool scene in Passengers is probably one of the most bonkers I’ve seen), but generally speaking, it’s taken for granted that there’s some technology that lets everybody walk around.

There are practical reasons for this. If you don’t have the budget to animate a rotating ship module, or the tools to mimic zero G realistically (as was so masterfully done in Gravity), it’s easier to wash your hands of the topic.

But the conversation about gravity doesn’t end there. The very design of your ship depends on it. You have to decide if your ship is capable of planetary excursions — meaning it has to be strong enough to handle a trip through the atmosphere, and then it has to be structurally tough enough not to snap in half while under the effects of gravity.

Serenity from Firefly can hop around on any planet it likes, coming and going as its crew smuggle things and otherwise engage in misadventures. So, too, can many of the smaller ships in the Star Wars universe, or the various shuttles in the Star Trek universe.

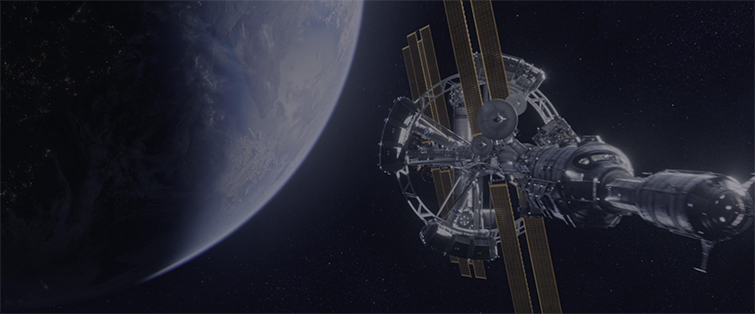

But the Hermes, from The Martian, was clearly built in space by assembling modules — not unlike the construction of the International Space Station. It’s easier to build something in space than it is to get it through the atmosphere in one piece. If the Hermes made it through re-entry, gravity would snap it in half like a twig.

Films break these rules all the time. In the Star Trek world, ships are typically built in shipyards in outer space, like Utopia Planitia. But in Star Trek (2009), we see the Enterprise under construction down on Earth. The more futuristic and less-grounded your ship designs are, the more you can get away with.

Let’s See Some Starships!

Now that we’ve established the general idea that form follows function in ship design, let’s take a closer look at the design part.

There are aesthetic decisions behind every Hollywood starship — just as there would be in real life. Remember: the ship is more than just a set piece — it’s critical to the story itself. That means its appearance will probably help advance that story, even if only subtly.

Wind resistance and aerodynamics aren’t a part of space travel. That means ships don’t need a shape that makes them faster the way jets do on Earth. Instead, their designs might try to do things like minimize their line-of-sight profile (for sneaky ships), maximize freight space while minimizing habitation (for cargo ships), or even just look intimidating.

Ships can be any shape you want — provided that they aren’t expeditionary craft that like to land on planets. That’s a different can of worms, and you need to keep weight distribution, flight capability (there’ll be atmospheres of some kind down on those planets), and durability in mind. (Planets and atmospheres are notoriously rough on spaceships.)

So, let’s look at a few iconic starships from cinema history and see how their designers used them to enhance the stories they serve.

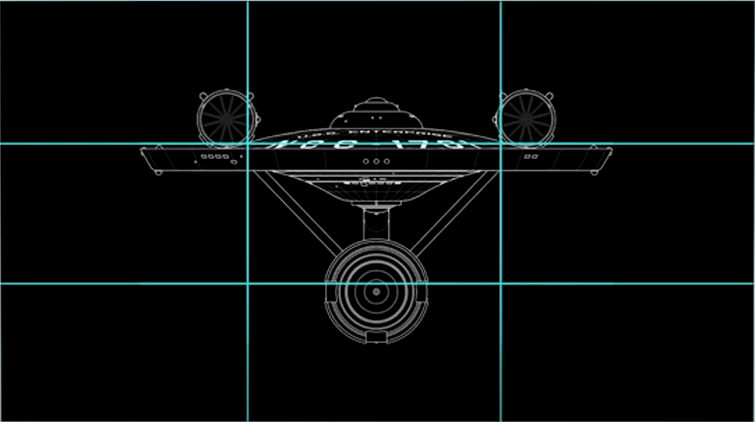

U.S.S. Enterprise

We’ve already mentioned this hallmark of cinema starship design, but it bears revisiting. Originally, the Enterprise was going to be the “Yorktown,” but Gene Roddenberry was so enamored with the actual Enterprise that its name won out in the end.

Interestingly enough, the NCC-1701 registry was inspired by the international aircraft registration assigned to the United States, “NC.” The second C in NCC is for the Soviets, who also used Cs in their registration. Matt Jeffries, the designer of the starship Enterprise thought that any meaningful venture into space was going to be a joint effort between the U.S. and the Soviets.

Incidentally, Jeffries was not a fan of science fiction, so when he began the project, he based his ideas in aeronautics. Roddenberry’s creative direction was peculiar: he wanted no rocket engines, no fire, no smoke — he did not want the ship to look anything like a rocket. So, Jeffries had to envision what a few generations of aeronautical engineering might look like. The famous roadster look with the sweeping nacelles and flattened saucer was the end result.

But none of that is what makes the Enterprise’s design so unique. What does is that it looks good from every angle. By adhering to the rule of thirds, Jeffries (perhaps unintentionally) designed a ship that looks aggressive and futuristic from every conceivable visual angle. YouTuber EC Henry demonstrates what I’m talking about in this fascinating video.

In the case of the Enterprise, form follows function, but it’s also aesthetically designed. That should be the goal of every aspiring ship designer. Make something that makes sense, and make it look good!

(You can check out the actual production model at the Smithsonian.)

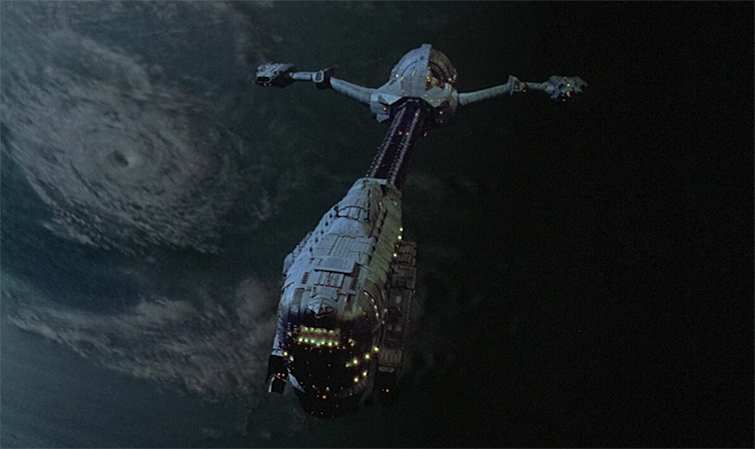

Discovery One

The development of Discovery One from 2001: A Space Odyssey is unique — Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke developed it in tandem for both the 2001 novel and its concomitant filmic adaptation. The realities of designing a spacecraft for a novel and designing one for a film revealed some interesting differences in how we think about these ships in different media.

Discovery One is a nuclear-powered, interplanetary spaceship, meaning it doesn’t have a warp drive that carries it out of the solar system. As would be the case with almost any craft of this size and complexity in the real world, it was built in and launched from Earth orbit.

Originally, Kubrick and Clarke considered a nuclear pulse propulsion system, but Kubrick demurred because including it might look like he was reversing the stance on nuclear weapons he presented in his previous film, Dr. Strangelove — so, you know, ship design isn’t always about form following function. Sometimes, it’s about reputation . . .

Discovery One adheres to the design tenet that you should keep your propulsion reactor well away from the crew, so it’s housed at the tail end of a long truss that attaches it to the crew compartment. The ship has a complement of two (as well as HAL 9000, the supercomputer that . . . causes problems in the film), and it features a rotating, moon-level gravity flywheel that contains the primary crew area. There is an automated kitchen (developed with help from General Mills) as well as hibernation pods for long travel times.

Most interesting for us is one of the key differences between the ship design for the novel and the ship design for the screen. Clarke included cooling fins for the thermonuclear propulsion system that “looked like the wings of some vast dragonfly.” The overall look was similar to an old sailing ship. Kubrick, however, ditched the fins because they looked like wings, which would suggest that the ship was capable of atmospheric flight.

So, that long, sleek, serpentine look that we’ve all come to know so well is the filmmaking analog of pulling the wings off of a dragonfly. How morbid.

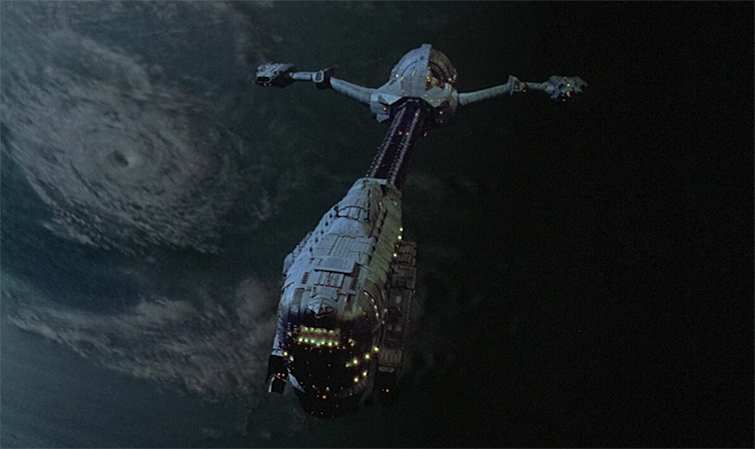

Event Horizon

This is another ship in our post here that needs a closer look. Let’s get meta for just a second.

Typically, when you’re writing one of these blog posts, there are some rules about images that you try to follow. You want some kind of image every few paragraphs or so (or a video embed) so your readers aren’t just scrolling through a block of text. As fascinating as those of us in the content marketing business think our writing is, there just aren’t attention spans to support those kinds of dissertations anymore.

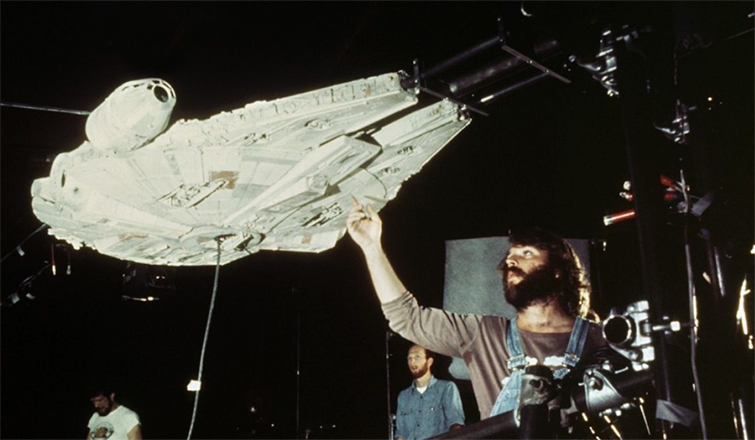

You also tend to vary your images and even include some that are only tangentially mentioned in what you’re writing about. For example, I could do a whole section on the Millennium Falcon design — it’s one of the most famous starships in science fiction film history — but there isn’t a whole lot to say about it other than what I already said:

The design of the Millennium Falcon famously drew inspiration from WWII-era bombers. (Image via Disney.)

Don’t forget to always attribute the image rights — you don’t want to get in trouble! But, back to the point, rather than make up a bunch of stuff, it was just more direct for me to include a picture and that punchline: “drew inspiration from WWII-era bombers” and then move on. Easy peasy.

You’re also not really supposed to repeat images unless you’re marching your audience through a tutorial or something, but we’re about to throw all these rules out the window because what I want to say about the design of Event Horizon is so perfectly captured in the image we’ve already seen that we need to see it again . . .

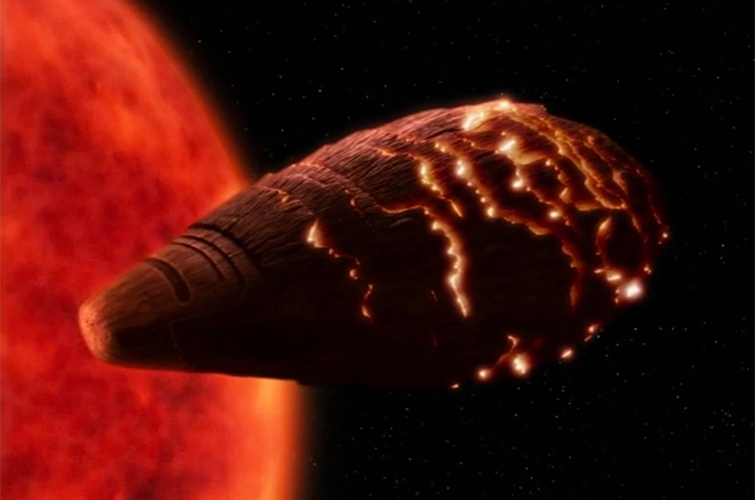

This ship follows all of the conventions. Its reactor is well away from its crew, it’s clearly designed only for interstellar travel and not atmospheric flight (it would snap in half just like the Hermes or the Aether, mentioned above), and its hull isn’t aerodynamic. Everything checks out: form follows function.

But it’s also a cool-looking ship, and the story itself heavily influenced its design. Here, I need to spoil the movie for you, but to be fair (“To be faiiiiir!“), you’ve had 25 years to watch it! This is a horror/sci-fi hybrid, and the ship goes to hell and comes back. This was not a pleasant journey for the crew. The rescue ship that approaches Event Horizon after it returns, the Lewis and Clark, faces the unpleasant responsibility of figuring out what happened to Event Horizon.

Let’s repeat: “the ship goes to hell.” So, where did the designers draw their inspiration?

What we did was to scan elements of Notre Dame Cathedral into the computer, so the thruster pods at the side were actually towers from Notre Dame … when you pull back, you see the crucifix hanging above Neptune.

That’s right. In a movie about a spaceship that goes to hell, the designers A) followed all the conventions of ship design and B) scanned in the world’s most famous medieval cathedral, which they then disassembled and reassembled to make their spaceship that goes to hell. Look again at the image. It’s a dark crucifix hanging in space.

Form might follow function, but it can also follow fiction. Event Horizon is a master example of telling a story through the ship design, onboard which your characters will enter a small pocket world (your set) where anything is possible . . . insofar as the ship allows it . . .

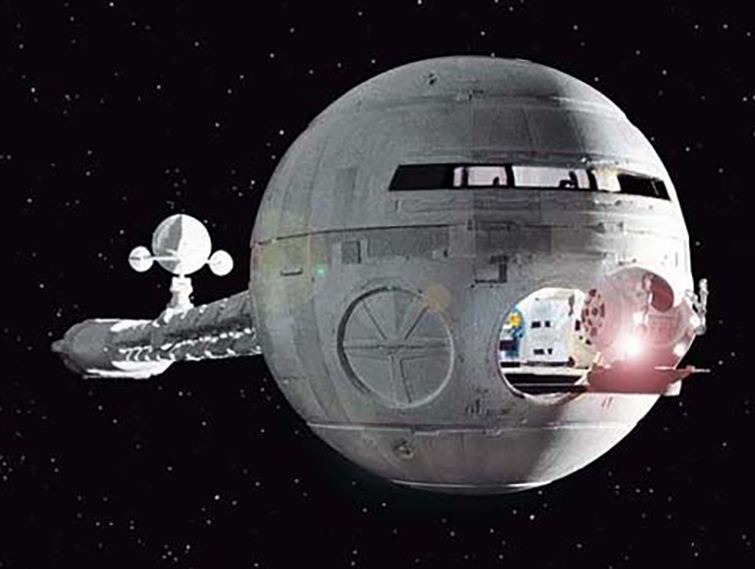

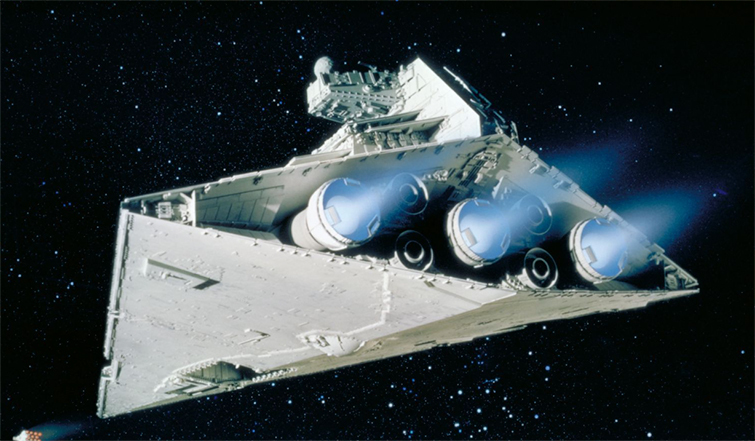

Imperial Star Destroyer

There are many ships in the Star Wars universe to admire, but we can’t cover them all here. The Death Star would be a little on-the-nose. Its whole thing is that it’s big, looks like a moon, and can blow up planets. It’s really a starbase, not a starship, so, we’re going to leave it out on a technicality.

Instead, let’s talk about one of the most awe-inspiring vessels in Star Wars: the Imperial Star Destroyer. As we mentioned above, many of the ships in Star Wars were inspired by WWII-era naval vessels and aircraft. The Star Destroyer is no different. Designer Colin Cantwell created this menacing space dagger by studying the decks of aircraft carriers.

The Star Destroyer that we know and fear is actually the combination of two different ship designs: a small, two-man fighter (the “Stardestroyer” — one word) and a much larger Imperial Cruiser, which launched the smaller ships like an aircraft carrier. Cantwell eventually merged the two designs.

Star Wars plays kind of fast-and-loose with space travel and aerodynamics. In later films, and shows, these massive ships can just hover in the atmosphere. It’s a cool effect, but it isn’t supported by any kind of imaginable design (not that this should ever limit our imaginations). Imperial ships are typically sharp and angular, and they look like they stab their way through space. (Rebel ships look more organic.)

One can easily see how Cantwell essentially transplanted a carrier tower, complete with its sensors and communication arrays, directly onto the arrowhead shape of the primary decks. He used a process called “kitbashing” to pull off this look. Basically, it means stealing parts from several different models and creating a new, unique design.

The end result is effective. This ship looks like a weapon, and it’s bristling with firepower, so even smaller, more agile craft have to be careful when they cross its path — which happens pretty often in the Star Wars universe.

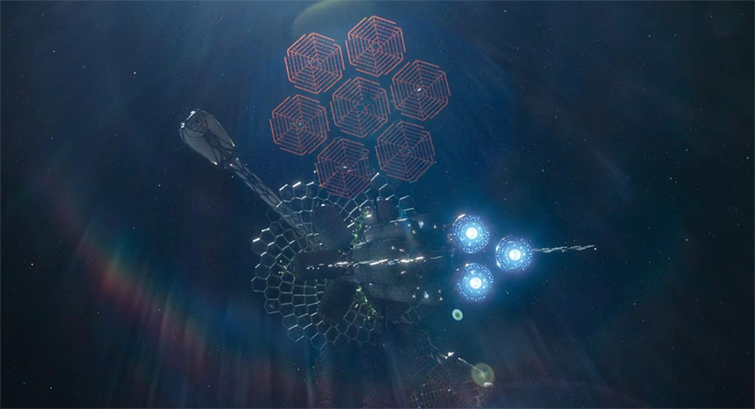

The Borg Cube

For my dime, the Borg are one of the most-fascinating, most-menacing enemy races in all of science fiction. They are a living disease, a race of parasites that seize other living beings, augment them with technology, strip away their identities, and absorb their cultures into their collective consciousness. It’s the quintessential nightmare of the digital age — being subsumed and rendered voiceless by the technologies that seem to rule our lives.

So, they need a ship that characterizes their worldview and how it relates to interstellar travel. Boy, do they have one.

The Borg Cube is unique among the unique. Just as the Borg themselves piece bodies together by seizing or salvaging others a la Victor Frankenstein, so, too, do they build their ships this way. The Cube is an agglomeration of inter-connected elements pieced together entirely based on function. There is no ship design here—there are no aesthetics. There isn’t even a bow or a stern. This ship is all sides at once, and it can spring into motion in any direction.

The ultimate pack-rats, the Borg simply add things onto other things until they become functional new . . . uh, things. Things like a nearly undefeatable starship.

The original concept is the brainchild of writer and producer Maurice Hurley, and actual first design is the work of Richard James. Working on simple notes that suggested the ship would be cubical, Hurley and James were able to use the story of the Borg themselves in the visual design of their ship. Rarely is the union between a ship and its crew so plainly evident. It’s a horrifying monstrosity of a starship — an ingeniously conceived and constructed horrifying monstrosity.

What Now?

After you’ve designed it, it’s time to build your ship. You can either create a model, which has long been the tradition in science fiction filmmaking, or you can use 3D rendering applications to design it on your computer. Kitbashing is a great way to get your hands dirty and actually get a feel for your ship, even if you do plan to create a digital render. Having both will definitely help you cover all of your bases.

If you haven’t already written your script, that’s next. You’ll need to develop your story, then type up your script. Of course, you’ll spend plenty of time revising, right?

Now, film in hand, you’re ready to go to space. We’ve taken the liberty of rounding up the assets you’ll need to create your own believable version of outer space. First, grab this free pack of 40+ space assets. You’ll find all the bip and bobs you need to detail out your universe — things like starfields, nebulae, etc.

Next, you’re probably going to need some planets — they tend to come up in science fiction plotlines fairly often. We’ve prepped a tutorial for you on how to do this . . .

And that should just about do it. You know how ship design works, you know the importance of the narrative in the design process, and you know how to create a universe for your ship to navigate. Get out there, and show us what you’ve got!

Cover image via 20th Century Fox.

For more on all things space, check out these articles

The Space Western — Genre’s Unwanted, Weird Cousin

SPACE KIT: Download 40+ Free Space Textures and Elements

5 Tips for Taking Care of Your Lenses in Outer Space

From the Moon to Galaxies Far, Far Away: Miniatures in Space