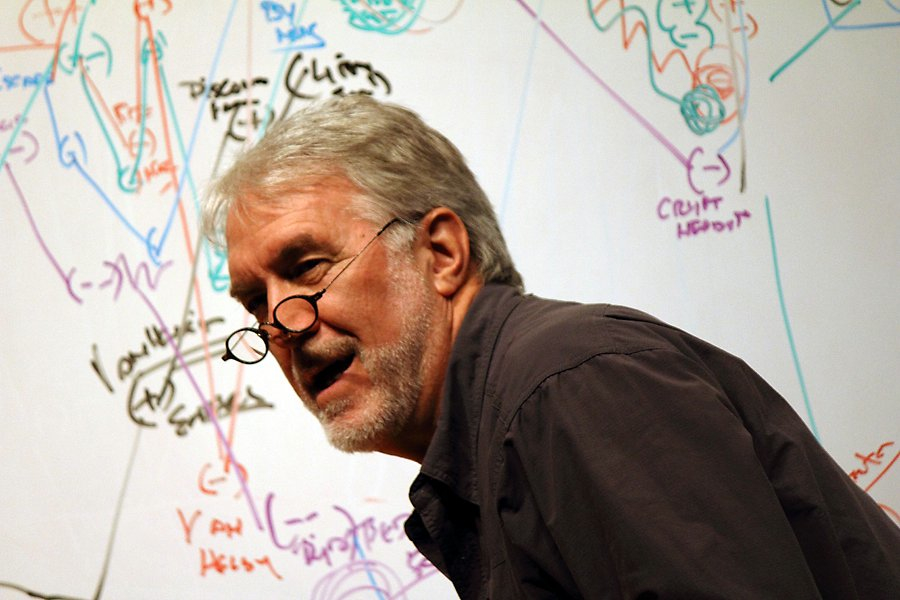

Screenwriter James V. Hart on Career, Coppola, and Creating a Method

James V. Hart has worked with many of the greats — from Coppola to Spielberg. We sat down to talk about his journey and some of the lessons he’s learned.

With experience ranging from Dracula to Hook (and many more), screenwriter James V. Hart has collected a wealth of knowledge and a fully formed workflow for taking an idea through inception to all three acts on the page. We sat down to ask him about his experiences, his approach, and what he’s valued most throughout his career.

PremiumBeat: I need to ask you about your first credit, Gimme an F, which seems to be a cheesefest in the vein of Porky’s meets Flashdance. How did the guy behind Contact, August Rush, and Dracula create a script about a bunch of randy cheerleaders complete with savage dance numbers?

James V. Hart: Yikes. Would you believe it is a cult classic to horror gore auteur Eli Roth? I wish they had shot the original script that I wrote, which was more like MASH, Slap Shot, Hangover — really a savage comedy about my confessions as a male cheerleader during my years as an instructor for the National Cheerleader’s Association in the ’60s. I was a cheerleader in high school in Ft. Worth and at SMU. I had to become one of the girls — gave me a whole new POV and appreciation for [women] and how they spoke and their views on boys and men. It was not just an exploitative sex romp, and it was really raunchy. The male producers could not believe girls and women could talk and act like the female characters. Cut to The Wedding Party and Mean Girls decades later. It was the last comedy I wrote. It was a racy, savage, love poem to cheerleaders everywhere.

PB: So many of your films involve larger-than-life characters and otherworldly locations. When you inhabit storytelling, are you most interested in diving into a world outside of yourself, or do you bring aspects of Jim to vampires and pirates and boys who never grow up?

JH: Unfortunately, every writer, including this guilty one, brings themselves to the table. Never grow up, never give up is one of my mantras. And, once a pirate, always a pirate. I am writing my fourth adaptation of Treasure Island for David Oyelolo, who is portraying Long John Silver as a man of color during the formation of the first democracy formed by pirates in the Caribbean in 1710, and where no slavery was allowed and everyone was equal, regardless of color — equal vote, equal shares of treasure. 150 years before Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation. My kind of pirates.

Hook was seminal for me. I could never have written Hook until I had kids. I will say this, one of my producers on Hook was impressed Coppola was directing at the same time Spielberg was completing Hook. I explained that Dracula was the dark side of Neverland, and she quickly corrected me by replying, “I think Dracula is the dark side of you.” Rimshot.

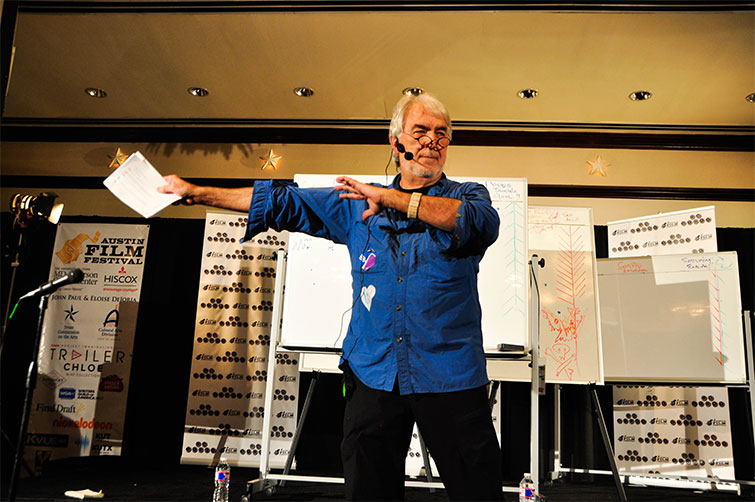

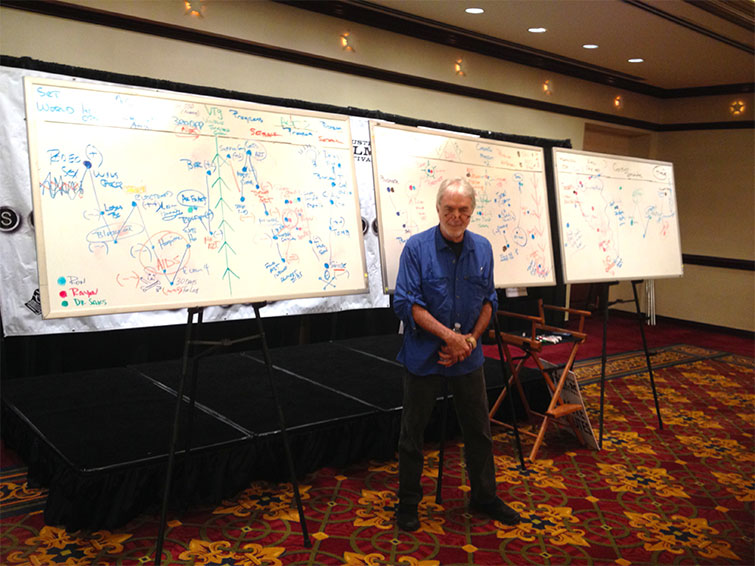

PB: You’ve created a very successful working process that you are sharing with other writers now called The Hart Chart — a system that you first discovered after working with Francis Ford Coppola on Dracula. Can you give us context to that discovery and how it changed your approach to storytelling?

JH: 1992. I get a phone call at midnight in NYC. It is Francis Coppola. He has been in post-production on Dracula for several months, and it is not going well. Another disastrous preview has the studio on edge. He asks [politely commands] me to get on a plane and come to San Francisco. He hates the film, hates the script, hates me for writing it, hates the cast, hates the studio, and he wants to show me the film to prove it.

“Great, I can’t wait to see it,” I replied facetiously.

It had only taken me 15 years of rejection and failure to finally get Dracula produced. And now one of the greatest directors in history of filmmaking was at the helm of a disaster in the making. How was that possible? What had gone wrong?

Image via Dracula (Columbia).

The next night I met Francis at the Zoetrope building on Kearny St. in San Francisco. He escorted me to the basement screening room, the Godfather room, with big leather couches, cigars, wine, brandy, and two women who spoke only Romanian, and he made sure I was comfortable with instructions to call him in his penthouse after I finished watching this film he hated and he would join me to discuss.

He was right. For 2 hours and 10 minutes, I watched the worst piece of shit film I had ever seen. I was comatose, destroyed, drunk, and pissed. Coppola finally called the screening room since I had not made contact.

I confirmed his opinion: “I hate you, I hate the script, I hate the actors, I hate the studio, I hate myself for writing it . . . etc. etc.”

This is midnight now, and Francis descends from his mountaintop and joins me for the aftermath. And then with complete delight and enthusiasm, Francis Ford Coppola tells me the story of the film, Dracula, that he wants to make.

I laugh, I cry, I puzzle. He tells me the story of the script I thought I had written, and the film I thought he had directed as I had seen the dailies and been on the set for much of the production. A little late to start over with an October release date less than four months away.

Image via Dracula (Columbia).

He invites me into the editing room to spend the next week reviewing every scene shot, other footage not used, etc. in service of the narrative Coppola had pitched and the script we shot. We targeted a dozen pieces and shards of narrative missing in the footage and the script, including story and character moments that had been cut from the script for budget, time, or our not thinking the moments were necessary.

We revised the shooting script with the existing footage in the editing room and wrote new pieces, bits, inserts, tags, beginnings and ending of scenes into the narrative that we had somehow missed in the scripting and shooting stages of the production.

Coppola skillfully convinced the studio that he needed to bring the cast together and shoot these narrative revisions at a substantial cost to deliver the audience a satisfying ending and, of course, to help the studio recoup their millions in production costs.

The best example of the problems the original shooting script did not reveal is the ending as the film was viewed in its initial release. This complete ending was not in the shooting script and went through several stages of additional development to arrive in its final form.

The solution to the ending came from an unexpected source — a “Resurrection Opportunity” in HartChart language, a true “Cinderella Moment” to invoke another HC signpost.

Coppola screened an improved cut for George Lucas and Mike Mignola (then an up-and-coming graphic novel artist — before he created Hellboy). Lucas nailed what was wrong with the ending. We had broken the rules of how to kill a vampire that we had established in the film; the only true way to kill a vampire is to cut off their head and cut out their heart, then burn it. Which is exactly what Van Helsing and his Vampire Killers do to Lucy in the film.

Lucas was spot on. The rules were right there on the screen. In order for Mina to give Dracula peace, she has to cut off his head with the Bowie knife she had plunged through his heart.

That meant bringing Winona and Gary back together to shoot the new moments and bits we needed to complete the narrative. Gary and Winona had literally been at each other’s throats since the second week of shooting. They had even refused to pose together for the photo shoot with the famed Albert Watson to be used for the poster promoting the film. They would never get together again for additional filming.

I remember Coppola calling me with this proposition:

“Do you think we can get Winona back to cut off Gary’s head?”

“It’s the only way you will get her back,” I replied.

Image via Dracula (Columbia).

Months after principal photography had been completed and sets had been struck, Coppola assembled a crew, including cinematographer Michael Ballhaus, and the cast, including Anthony Hopkins, Gary, and Winona — all one big, happy family — back at Sony studios in Culver City, CA. The missing parts of the narrative were filmed, including Winona cutting off Gary’s head.

Coppola’s mastery and execution is seamless. In the film’s climax when Mina decapitates Dracula and sets him free, there are close-ups, medium shots, and high angles that were filmed almost a year apart. The same for many other narrative pieces Coppola captured and edited into the final version.

Bram Stoker’s Dracula opened in October of 1992 to a record-breaking $32m and went on to gross $215M worldwide on a $40m dollar budget. It was the ninth-highest grossing film that year.

But what haunted me was the nagging questions about the faults and inadequacies of the script during principal photography that were only discovered in the editing room during post-production. There had to be a method, or a tool, or a program that could be applied in the development stages that could potentially head off these kinds of creative crises. And if there wasn’t, there should be.

Certainly, lower-budget indy films do not have the resources to bring together cast and crew a year later to re-shoot and/or shoot new material like Coppola did with Dracula. Indy filmmakers would kill for a way to get it right on the page and save time and money during principal photography and post-production.

I was determined to find, steal, or create a method, a tool, a philosophy that could highlight these problems in the script development stages and address them prior to production.

Image via Dracula (Columbia).

In my discussions with Coppola, he gave me the key: the three magic questions to ask and answer about your characters before writing the script.

- Who is the main character(s) and what does he or she want? (What they need is different; see below.)

- Who are the characters and the relationships and what are the obstacles the main character must encounter and overcome in order to get what he or she wants?

- In the end, does the main character get what he or she wants or not? Is it good or bad for them if they did or did not? (i.e. Did he or she get what they need?)

I realized that by answering these questions about each main character in my narrative, I would be creating a character-driven three-act narrative (or 7- or 10-act), rather than plot-driven.

The emotions, desires, wants, and needs of the characters would be the story engine instead of a plot imposed on the characters by the writer.

My characters would pull me through the story rather than push me.

By adding more questions and narrative signposts, I had a tool kit different than any screenwriting dogma I had encountered that presented rigid rules and formulaic results: “By page so and so you must do this. The inciting incident must occur before x.”

I was liberated to let the characters structure their journey, (not the self-imposed plotline).

Literally, my own heartbeat added the final ingredient to the story brew of the HartChart. While having my annual heart exam and EKG, I watched the needles tracking my pulse on the graph and posed to my Cardiologist I should wire myself up when I watch a film (or now binge-watch TV) and see how my heartbeat is affected by what I am seeing and experiencing.

Then the epiphany, lightbulb, a ha moment: could I measure/forecast the heartbeat of my characters as I was writing the script and plot their emotional journey on a chart like my EKG? (i.e. take the pulse of my characters in any scene or sequence and measure their ups and downs, victories and defeats, progress and setbacks from beginning to end!)

PB: That was amazing to hear. In a way, you’ve already answered my next question by going through the Hart Chart, but we often hear that writing is re-writing. What is your process after you have a first draft that makes you satisfied? Do you have a trusted source read it for feedback? Or is your process back to basics, back to the chart? When are you satisfied that you are done and ready to hand the script off to executives or the director?

JH: First I use the HartChart tool kit and the story-mapping tool to do my own autopsy on the draft. I use those tools every day. I apply the audience test to the read, which is new for me. I apply certain audience questions as if the audience is looking over my shoulder as I read/write. What do they know? When do they know? How do they find out? Are they satisfied?

I also have a handful of close confidants and family I will entrust to read. They are tough and honest, which is what you want in order to succeed at any successful revisions.

Image via Dracula (Columbia).

PB: Much of your work has been adapting existing material — what are the challenges you face when going from a book to screen or taking an iconic character such as Dracula or Peter Pan to a screenplay?

JH: Significant baggage. There were over 100 Dracula films and gobs of books, comics, and games, embedded in the audience before I even wrote a word. Same for Hook — a grown up Peter Pan? Blasphemy! The biggest problem with adaptations of pop icons and massively popular characters and stories that the writer is competing with [. . .] is the mind of the viewer. The best movie of any book etc. is in your head. That is who were are competing against — the imagination is a powerful cinema experience.

Image via Epic (20th Century Fox).

PB: As a man who has been married to the same woman since 1973, you are obviously a guy who commits and can collaborate. You’ve worked with your friend Bill Joyce on Epic and with your son, Jake, developing projects. What’s the secret to writing with someone else, especially someone to whom you are very close?

JH: Judy from the beginning was a great cheerleader for my work, and my harshest, most honest critic. She is busy being Bo — her grandmom name — to our two grandsons, who are currently on location with their mom, Julia, our writer-director daughter. Jake has been a collaborator since age 6 when he asked “What if Peter Pan Grew Up?” Finding a rhythm and a trust, and being able to debate and disagree, and argue, and butt heads without taking it personally is the most difficult balance to find. When it works, and have those breakthroughs and Cinderella moments and bliss hits, you have someone you really care about to high five with.

Image via August Rush (Warner Bros).

PB: Finally, writers are often marginalized in the process once they’ve handed off the script. What film has been your most complete experience of being respected and involved with the final product? Or is that question even relevant — should writers just let their babies go?

JH: Dracula and working with Coppola was the most satisfying complete experience I have had or will ever have in my writing life.

Working with Brian Henson and the amazing Muppet players and the entire Henson family and company was the happiest I remember being on and off the set.

Standing in Central Park at night with a full orchestra playing Mark Mancina‘s “August Rush Rhapsody,” watching Freddy Highmore bring his parents together with his music is about as good as it gets.

Hook was seminal to my career and my family and Mr. Spielberg, who does not like Hook, will always be in my long list of thank yous if there is ever the right occasion.

The two years I had with Carl Sagan and Anne Druyan on Contact can never be surpassed.

Go with gravity. See where it takes you. It has certainly been good to me.

Cover image via James V. Hart.

Looking for more industry interviews? Check these out.

- Screenwriter Norman Steinberg on Mel Brooks, Richard Pryor, and Getting Heard

- Jonah Hill on Writing and Directing Mid90s — and Tips He Learned from the Greats

- Interview: Jennifer Gatti on Bon Jovi, Star Trek and Longevity in the Business

- Industry Interview: Advancing Your Career from PA to AD

- Best F[r]iends: Greg Sestero on Making Movies With Tommy Wiseau