Tips on Cutting Comedy Projects from Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee

In which we highlight a few tips on cutting comedy projects based on Jerry Seinfeld’s “Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee.”

Cover image via Netflix.

Learning to tell a short joke is a big lesson in storytelling. Each joke has its own setup, elaboration, and punchline. It’s a classic three-act structure: beginning, middle and end.

Editing is crucial to telling a joke successfully on film because comedy is all in the timing. If the rhythm of the storytelling is wrong, a funny joke can fall flat.

Although we most often think of jokes in the context of stand-up comedians, or simply telling a friend a funny story, we are actually all “editing” in real-time — adding pauses for laughter, leaving things out that hinder the story, and adding emphasis to make sure the punchline really lands.

In this post, I’ve brought together some compelling insights into constructing and cutting comedy — largely based on Jerry Seinfeld’s Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee and the Ghostbusters remake.

In this short interview with the New York Times Magazine, Jerry Seinfeld breaks down his writing process when constructing a joke.

Although he’s going for as many laughs as he can, Seinfeld says, “I know you think people are going to be interested in this . . . but they’re not.” There are some useful tips here on understanding how a joke works that can help you keep from harming the humor when you’re editing one. And as an editing mentor of mine likes to say “Always keep in the funny.”

Make the First Line Funny

“When I was a kid and they invented the pop-tart, the back of my head blew right off.” Depending on the context of the piece you’re editing, you usually don’t want a joke to sidle up to the audience. You need them to know you want them to laugh — that they’re supposed to laugh.

(Incidentally this is why watching something like the original Coen Brothers film Fargo gets funnier with every watch. When you first watch it, you think it’s a thriller, and you don’t know you’re supposed to be laughing.)

Use Funny Words

“Chimps in the dirt playing with sticks. In seven words, four of them are funny.”

As much as we want to make comedy sound complicated, most of the time, we’re laughing at people falling down, saying funny words, or making strange sounds. If a word is funny (“kumquat” for instance), go with it.

Timing Is Editing

“So now I’m looking for the connective tissue that gives me a really tight, smooth link . . . if it’s just a split-second too long, you’ll shave letters off words. You’ll count syllables.”

Cut out anything that gets in the way between the setup and the punchline. As we’ll see later, even a few extra frames can ruin a joke.

The Biggest Laugh Has to be at the End

Even though Jerry is talking about writing “a long bit,” this is true of any comedy scene. You want the biggest laugh at the end of the scene — otherwise it will drag on, and the final delivery won’t be worthwhile.

This is similar to the editing maxim of “arrive late, get out early.” You want to cut out all of the “shoe leather” (people walking to the door to open the door to enter the office to sit in the chair to start talking) and just cut to them in the office talking.

To waste this much time on something this stupid, that felt good to me. —Jerry Seinfeld

Editing Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee

If you’ve never seen Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee, it’s now on Netflix (it was originally online for free), and the basic premise is that Jerry takes a different comedian out for coffee in each episode — and they try to make each other laugh.

It’s a “talk show interview on the move” with a set structure that lends each episode some semblance of a format — albeit a very fluid one. Since it was originally for online audiences, there is no specific runtime — no need for ad-breaks, recaps, or cliffhangers.

As such, it’s an interesting show to watch from an editing perspective because it’s almost always just about cramming in as many jokes as possible without much narrative drive. (We’ll look at some specific examples in a bit.)

In this hour-long discussion between Jerry Seinfeld and David Letterman, hosted at the Paley Center for Media, you can learn how Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee came to be — and what it takes to make each episode.

It’s worth watching for a few minutes from about 9 minutes in (click here), as you’ll not only get Seinfeld’s rationale behind the look of the show, but you’ll also get a few stats on the shooting ratio.

For each show, they generally shoot for 3-4 hours and compress that into 10-20 minutes of final product. Seinfeld says that it usually takes them about three weeks to edit each episode. Since there is no “network formula” they have to meet, they can make each episode as long or short as it needs to be.

What’s really interesting, and what makes this particular video worth watching for our purposes, is that (at 10.40″ in) Seinfeld shows a 60-second clip of unedited raw material and then the same footage edited into the show.

It’s not often that you get to see these kind of comparisons. It’s instructive to see how they edit the show to create a driving pace — as well as cutting straight to the jokes.

(There is a second example at 15.42″ of Seinfeld and Sarah Silverman in a doughnut shop.)

Seinfeld mentions (and it’s obvious in the second example) that many of the scenes are actually music montages with jokes and one-liners for good measure. For Seinfeld, this is because there is no “driving” force behind each scene — it helps to move things along.

It’s also interesting to note that all of the social media experts Seinfeld consulted before beginning his experimental show (“I honestly didn’t know if it was going to work.“) told him that shorter was better for the internet, while I suspect he had a show more like Seinfeld in mind, which ran for 20 minutes per episode.

Jerry: You can’t make it longer than 5 minutes. If you make it longer than 5 minutes the audience is going to be gone . . . and I ignored that. They said ‘5 minutes is the internet firewall, you can’t go past it.’

David: They have quantified the American attention span as five minutes?

Jerry: Yeah, but our viewers on average watch 19 minutes.

Dissecting a Frog — Analyzing a joke

In this excellent post, Tony Zhou of Every Frame a Painting compares the opening 18 seconds of the U.S. and U.K. trailers for the 2016 Ghostbusters remake.

The reason this post is worth reading is that it demonstrates the difference that a few frames can make when selling a joke. It also shares some excellent lessons on why a joke’s setup may be the reason for its failure.

(Jump here to read through the full breakdown, including frame count and shot composition comparisons.)

Tips on Editing Interviews and Action for Laughs

In this excellent breakdown by Thomas Flight, you can see a comparison of two different interview formats: David Letterman’s My Next Guest and Jerry Seinfeld’s Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee.

“When you’re making arbitrary cuts to arbitrary angles, we begin to notice the editing and the camera work, and it draws our attention away from the content of the interview.”

In the essay, Flight lays out three logical reasons why you might want to cut during an interview:

- To show relevant information (e.g. a reaction shot).

- A cut for punctuation and emphasis.

- Edit out mistakes or pauses to improve the flow of conversation.

These are also the reasons you would want to cut during a joke as well. If you’re not cutting for these reasons, you might want to ask yourself if you really need to cut at all.

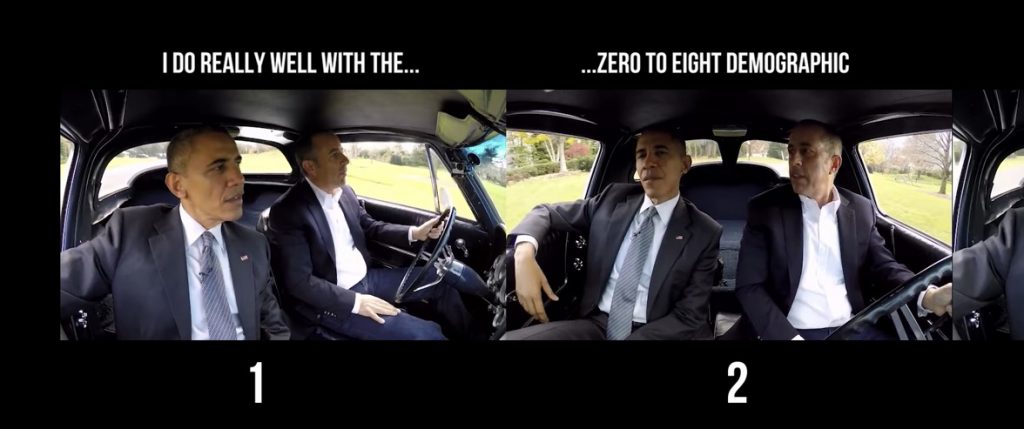

At 3 minutes into the video essay, Flight breaks down a moment from the episode of Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee with President Barak Obama. (Another excellent episode.)

Watching this breakdown will give you some great insights into a logical progression behind making edits that increases the power of the joke and helps the punchline land.

I’ve not seen anyone use this cut-by-cut, picture-in-picture technique before (to break down an edit), but it’s a really powerful way to see what each building block is doing and whether it’s helping or hindering the structure of the scene.

The most important part is the editing. And most of the directors they don’t know how to edit it. Even the stunt co-ordinators they don’t know how to edit it. —Jackie Chan

Also from Tony Zhou of Every Frame a Painting is a lesson from Jackie Chan on editing action and comedy for the greatest impact, which means “keep the action and the reaction in the same shot.”

This is a fundamentally different rhythm than Hollywood editing, but it’s far more successful. Zhou also covers Chan’s preference to add frames to action cuts to make the hits clearer and stronger — rather than adopting the U.S. style, which is to actually remove frames to make the cuts faster and more visceral.

Looking for more filmmaking tips and tricks? Check out these articles.