A Study of Unreliable Narrators Throughout Film History

Exploring the deceitful history of unreliable narration in film, and how you can use it to subvert audience expectations in your projects.

What if I told you that not everything you’re going to read in this article is true? Sure, it’ll be well-researched and well-informed. And, yes, we’re going to go over the history of film narration and the ever-popular unreliable narrator. But, what if we were to cast just a little bit of doubt as to whether you should trust us or not?

Maybe it’d be a bit harder for you to take this information at face value. Or, maybe it’d make the presentation of said information just a little more enjoyable, once you add in the mystery. Or, maybe you’ll simply be inspired to explore having an unreliable narrator in your own film and video projects as a lively way to spice up your narrative and sprinkle in some fun in your cinematic storytelling.

Whatever the case may be, let’s go over the roots of unreliable narration, trace out some of our favorite examples from some film classics, and dive into how you can write, shoot, and use an unreliable narrator in your projects.

What Is an Unreliable Narrator?

Before we dive into defining an unreliable narrator, we have to talk about film narration in general. In the beginning, when films were first introduced, they were silent. The main form of narration came through text on screen, which gave both direction, as well as shared the dialogue you’d seen in the previous scene.

Over the years, as film has added audio, narration is more often not needed as audiences can follow what’s going on through the action and dialogue between characters. However, we do still use narration from time to time. Yet, instead of a necessity, it’s become much more of an added element — at times, even an added character.

An unreliable narrator, by definition, is simply “a narrator whose credibility is compromised.” We find examples of unreliable narrators across film history, but also in other forms of art and literature even before that.

History of the Unreliable Narrator

Tom Hanks titular character in Forrest Gump could be classified as the “naïf” archetype for an unreliable narrator. Image via Paramount.

While one could argue that all narrators are unreliable to some degree, the first example of the term being used was in 1961 by Wayne C. Booth in his book on literary criticism called The Rhetoric of Fiction. According to Booth and other literary scholars, the unreliable narrator has indeed been featured across history in many different styles and forms.

Interestingly, you can actually break the unreliable narrator into five different archetypes, which have appeared across film and literature classics ranging from the work of Franz Kafka to Forrest Gump.

- The Pícaro: Narrators who are characterized by exaggeration and bragging. (Examples include Plautus‘ comedy Miles Gloriosus.)

- The Madman: Narrators who are either experiencing mental defense mechanisms or severe mental illness. (Examples include Franz Kafka’s narrators or Patrick Bateman in American Psycho.)

- The Clown: Narrators who don’t take narrations seriously and will play with conventions, truth, and the reader’s expectation for amusement. (Examples include Tristram Shandy and Bras Cubas.)

- The Naïf: Narrators whose perception is immature or limited through their point of view. (Examples include Huckleberry Finn and Forrest Gump.)

- The Liar: Narrators of sound cognition who deliberately misrepresent themselves, often to obscure their unseemly or discreditable past conduct. (Examples include Ford Madox Ford‘s The Good Soldier.)

Unreliable Narrators in Film

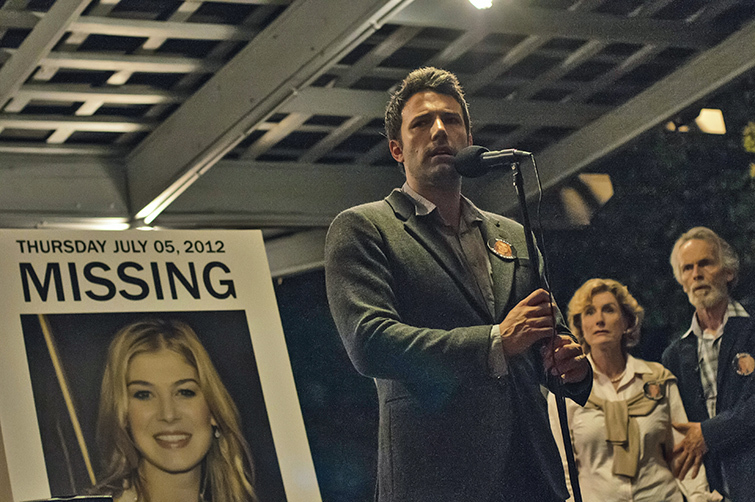

The dual narrators in Gone Girl are a perfect example of how unreliable narrators have been adapted from literature to cinema. Image via 20th Century Fox.

Furthermore, these classic archetypes are expanded upon throughout film history, as the narrative trope has become a bit more popular in modern and postmodern cinema, with filmmakers finding new and innovative ways to subvert audience expectations. Chances are one (or several) of your favorite films could be some of those classified as having unreliable narrators. Some popular examples include:

- Verbal Kint (The Usual Suspects)

- Jack Newsome (Room)

- Arthur Fleck (Joker)

- Francis (The Cabinet Of Dr. Caligari)

- The Narrator (Fight Club)

- Briony Tallis (Atonement)

- Teddy Daniels (Shutter Island)

- Nick and Amy (Gone Girl)

- The Narrators (Rashômon)

- Leonard Shelby (Memento)

Using some of the examples above, let’s dive into how you can add a standard unreliable narrator to your projects.

How to Write an Unreliable Narrator

When writing an unreliable narrator into your film or video’s story, you have plenty of decisions to make and lots of opportunities to explore this open-ended device. The only hard rules are that you must provide narration in some form, and that you must establish that — in some degree — it’s unreliable.

For presenting narration, you can use voice-over (VO), you can have a character break the fourth wall and directly address the audience, or you can try some text-on-screen approaches or other hybrid techniques.

Some tips for writing an unreliable narrator include the concept that you don’t have to always decide on using an unreliable narrator at the very beginning of your writing process. A great example is Fight Club, where the author of the original novel, Chuck Palahniuk, has admitted that it wasn’t until halfway through his initial draft that he realized his narrator would be unreliable (to put it mildly).

Filmmaking Tips for Unreliability

When it comes to filming projects with unreliable narrators, you have plenty of options and opportunities to use your unreliable narration to bring your audiences deeper into your story. As you can see in the video above, one of the best examples of how filmmakers can have fun with unreliable narration comes from Quentin Tarantino and how he plays with perceptions and storytelling in The Hateful Eight. We get some fantastic examples of how a writer and director can work together to sow seeds of doubt as to whether the events being depicted in the film are true to the narrative, or inventions of the imagination from one of the more deceitful characters.

We also have several examples of how filmmakers can use cinematic clues throughout their films to help undermine the credibility of their narrators. By sprinkling these little tales in different frames and in different representations of characters and their performances, a good director can create a strong sense of unease, helping to build the drama and suspense of a film toward a very rewarding climax. If you’ve ever seen The Usual Suspects, you know what I’m talking about — every small clue laid out in the film adds up to a surprising end-reveal.

Whatever your style or approach may be, it’s up to you to decide just how you want to tell your stories, who you want to tell them to, and if you want your audiences to trust your narration — or if you’d rather have some fun with their expectations and help create something much more challenging and entertaining, at the same time.

For more tips, tricks, and techniques for narrative filmmaking, check out the articles below.

- 7 Reasons You Should Consider Adding Voice Narration to Your Film

- Interview: Tips for Blending Documentary and Narrative in “The Drug Runner”

- How to Capture The Narrative Power of Shutter Speed

- Understanding Point of View in Film and Video

- Film School 101: Filmmaking Fundamentals, Assignments, and Exercises

Cover image of Fight Club via 20th Century Fox.