The History and Power of Sound Design in the Film Industry

The history of sound design involves innovations from some of the biggest names in Hollywood. At the 2019 Tribeca Film festival, we heard their stories.

Last week at the 2019 Tribeca Film Festival, Making Waves: The Art Of Cinematic Sound premiered after nine years in production. Director Midge Costin takes audiences on a journey from the era of silent films to today’s blockbusters, with a painstaking ear to shifts in sound design trends and the influence of developments in technology. Making Waves feels like a 90-minute deluxe Hollywood backlot tour led by the scientists of cinema. It begins with the notion that sound is the first sense humans develop in the womb and ends with an encyclopedic guide to each function of the sound design department. Making Waves was a showpiece of this year’s festival, and it’s sure to become a classroom staple.

At pivotal points in cinema history, sound design pioneers Walter Murch (Apocalypse Now), Ben Burtt (Star Wars), and Gary Rydstrom (Jurassic Park) were artists with the passion and skills to move the medium forward, working against a studio system that did not value sound as a cornerstone worth funding or time. They and their contemporaries had to prove sound design’s worth by creating visceral experiences that could persuade even the most resistant gatekeepers. A handful of tricks disclosed in Making Waves changed the game forever.

The Fantasy Creature Question

Murray Spivack headed up the sound department at RKO Radio Pictures when the monster King Kong came across his desk. How could he create a roar that was believably animalistic yet somehow otherworldly, befitting the gigantic gorilla? Spivack ventured to Selig Zoo to make field recordings of a lion and a tiger. He used reverse playback and altered speeds, overlapping the sounds to make an ambiguous and terrifying sonic identity for the icon. King Kong (1933) was the first time sound effects were recorded specifically for a film in this way.

Spivack’s mark is everywhere. Ben Burtt was charged with giving wookiees a sonic identity for Star Wars (1977) and took a similar route with field recordings. He made a map of Los Angeles documenting where he recorded source material for the sound in the film, including wookiee language: a combination of walrus, lion, rabbit, tiger, and badger.

Jurassic Park needed this kind of magic, too. Gary Rydstrom employed animal noises he spent months recording to fashion the roars of the dinosaurs, which had to do justice to the sounds audiences were anticipating. Tortoises mating, horses breathing, geese screaming, a baby elephant’s sounds slowed-down — all these were original sources in the film’s sound design. There’s a thorough rundown of each Jurassic Park dinosaur species’ source sounds here.

Stubborn Barbra Streisand

Barbra Streisand in Funny Girl (Columbia).

The advent of modern sound design may not have been possible without Barbra Streisand. Making Waves includes her account of a pivotal moment on the set of Funny Girl (1968), when the singer insisted she track an onstage vocal live rather than submit to a dubbed performance. Dubbing was the norm at the time, and Streisand was past that. Her understanding of sound as a masterful recording artist — and her influence as a superstar — made her the ideal figure to push sound design forward on set. But she also helped change how movies were played in theaters with the 1976 remake of A Star is Born.

Before that film, moviegoers heard the sound from a single speaker behind the screen. Streisand knew about a new surround sound system designed by Dolby that was ripe for use in theaters. It was urgent, she thought, to unleash that technology on the cinema world. So she offered $1 million of her own money to prove what could happen if enough time and care went into the sound design before a revolutionary presentation of the film in surround sound. Warner Bros. was so thrilled with the soundwork effort that they ended up paying for it instead.

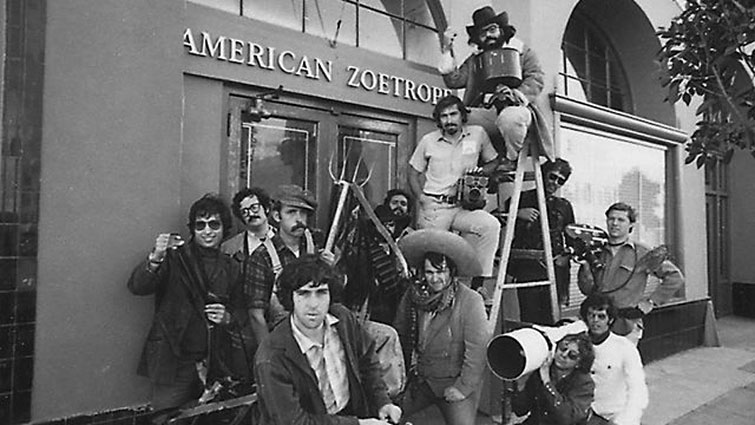

American Zoetrope

The founding of American Zoetrope by Francis Ford Coppola and George Lucas in 1969 cemented a formative alliance between the two directors and their close collaborators. Ultimately, American Zoetrope would produce films that established how important sound design was in the alchemy of a movie. THX 1138 and Apocalypse Now (1979) are two notable examples of experimental soundwork by Walter Murch, enabled by the bold directors of American Zoetrope, who banded together to make the kinds of films they wanted.

In Making Waves, Murch explains that he was not inspired by the cookie-cutter films that overloaded cinema houses when he was a kid in the 1950s. Instead, he was obsessed with the radio, recording bits and pieces of programs and splicing them together in non-linear collages he discovered later were part of the musique concrète tradition. George Lucas later befriended Murch at the University of Southern California’s film school, and the rest was history. You can hear the audiophile’s deeply psychological sensibilities in The Godfather. Just before Michael murders Sollozzo, the character’s internal impulse enters the sound design: the “firing of his neurons as he makes the decision,” as Murch puts it.

This was an early instance of POV-sound — sound design that gives exclusive insight into a character’s experience. The gruesome opening twenty minutes of Saving Private Ryan under Rydstrom is another storied example; The Pianist and Black Swan also feature killer instances of POV-sound ripe for study.

Cover image via Making Waves.

Looking for more coverage of the 2019 Tribeca Film Festival? Or more on the filmmaking industry? Check out these articles.

- Director Carine Bijlsma Got Personal With D’Angelo For “Devil’s Pie”

- These Tribeca Docs Will Renew Your Faith In The Power of The Camera

- Breakout Director Kat Candler on the Best Festivals for First-Time Filmmakers

- The Cameras and Lenses Behind the Marvel Cinematic Universe

- Industry Insights: A Conversation with Actor and Director Melanie Mayron