The Art of Split Screen

Film editors and VFX artists have used the split-screen technique for over 100 years. Let’s a look at its evolution during two prominent decades.

Top image via Universal Pictures

Split screen filmmaking is one of the oldest techniques used by film editors and VFX artists alike. Whether it’s editing clips together or building a single shot from multiple takes, here are some of the many different uses of split screen.

If you’re still unfamiliar with the technique, look at this video essay from Marco Heiter, which highlights many of the most famous uses of split screen editing.

A Brief History of Split Screen

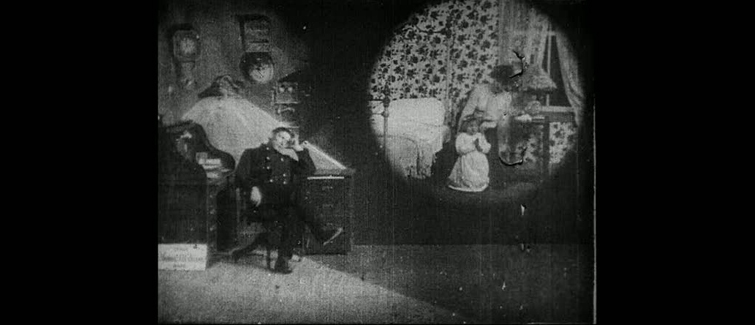

The use of split-screen filmmaking dates back to the 1890s. Early uses, like Edwin S. Porter’s 1903 film Life of an American Fireman, showed the thoughts of the main character. In fact, the film’s opening scene is the fireman thinking of a woman and child.

Image via Wikipedia

Magician-turned-filmmaker Georges Méliès used split screen along with matte paintings to composite his head several times in the 1898 film The Four Troublesome Heads.

Split Screen of the 1960s

In 1957, filmmaker Francis Thompson began experimenting with custom lenses to create his short film N.Y., N.Y. He used the technique again in his Academy-Award-winning film, To Be Alive, which played at the 1964 New York World’s Fair. Thompson never revealed his technique, but after the success of To Be Alive, split screen started appearing more often in countless films.

1958’s Indiscreet used the technique to get past censors. There were issues with scenes showing Cary Grant and Ingrid Bergman in bed together, so director Stanley Donen used a split screen. The actors were filmed in separate beds, but their conversations were carried out as if they were in bed together.

In 1961, the Walt Disney studio blew audiences away with The Parent Trap, which starred Hayley Mills and, well, Hayley Mills. Now, this wasn’t the first film to use a split screen to star two characters played by the same actor, but it was the first major blockbuster success to do so. Walt Disney demanded that the VFX not be visible, and the work paid off as The Parent Trap won the Oscar for Best Film Editing.

Here is a wonderful behind-the-scenes look at the making of The Parent Trap. Two different exposures using a black matte were primarily used, often hiding the split screen behind background elements like door frames and bed posts.

1966’s Grand Prix used split screen and is well known for its intro credits — which legendary designer Saul Bass did. Bass later criticized split screen and its overuse in the 1960s.

The point is, it’s a device, and as far as I’m concerned I’ll never use it again — if it actually cries out for it, I’ll use it but as a device it’s lost its currency, because, later on, it was, unfortunately, used meaninglessly. It’s the kind of thing that grows up without ever having a youth and there’s no opportunity to explore it. On Grand Prix, I took the multiple image …. and carried it down the line quite a way. I think it is terrific at expressing muchness, but I suspect it’s not capable of expressing deep feeling or contemplative…

— Saul Bass: A Life in Film and Design

One of the most famous uses (or perhaps overuses) of split screen came from the 1968’s The Thomas Crown Affair. The film features a “multi-screen” montage during a polo match. Designed and edited by Pablo Ferro, this sequence was created to cut down on the film’s run time. A fifteen-minute sequence was edited down to two minutes.

I had 66 images on a 35mm film. And that’s when Steve McQueen swings and hits the ball, and you see the whole thing. It was just so interesting seeing the whole swing.

— Art of the Title

As the 1960s ended, the use of split screen seemed to have run into the ground. It didn’t appear nearly as often, but when used correctly, split screen still earned critical praise for editors like Thelma Schoonmaker, who used the technique in the 1970 documentary Woodstock.

During the 80s and 90s, split screen was primarily used by VFX artists in films like Who Framed Roger Rabbit and Back to the Future Part II. (Check out the use of split screen with the flying DeLorean.)

Split Screen of the 2000s

As so often seen in this industry, a technique will quickly find itself run into the ground — only to later have a resurgence. For the split-screen technique, the success of independent filmmakers and the creation of new tools in programs like, After Effects, gave rise to its return.

In 2000, the film Requiem for a Dream crushed the hearts of every audience member as they watched a realistic fall into drug addiction. In one of the film’s more sentimental moments, Jared Leto and Jennifer Connelly intimately share a bed and the split screen is used to draw attention to the couple’s caressing hands. It’s the rare love scene that focuses attention on the lover’s embrace, rather than pure erotica.

The Rules of Attraction uses the split-screen technique in an unconventional manner. After a montage of split-screen clips, this sequence ends with two characters having a conversation. The audience sees the face of each character during the conversation, and then, with the use of a motion control camera rig, the split screen folds into a single shot.

In Kill Bill: Vol. 1, director Quentin Tarantino and editor Sally Menke use a wide variety of filmmaking techniques for each chapter. Throughout the film, several split-screen edits are used, the most well-known being the hospital scene. The image of the bride and nurse are juxtaposed, creating an overall eerie feeling during the assassination attempt. The combination of the whistling sound and split-screen edit became a defining moment for the film.

By the mid-to-late 2000s, split-screen editing and split-screen VFX merged in countless television ads and films. Kinetic typography was often included, such as this intricate sequence from Stranger Than Fiction.

In Edgar Wright‘s tribute to video game and comic book culture, Scott Pilgrim vs. the World features an incredible amount of split-screen sequences. Wright uses split screen for everything from transitions between scenes to “combo” fight sequences. In this final battle, an array of split screens are used.

While these are all uses that showcase the split screen, the technique is still used unnoticeably by directors like David Fincher. Fincher combines several actors’ best takes into one single shot. In this tutorial from Ben Gill, you’ll see how Fincher uses split-comping to combine three different frames in The Social Network or two frames in The Curious Case of Benjamin Button. Gill then shows you how to use this split screen comping.

For more tips and tricks, check out these articles: