Industry Interview: Documentary Editor Aaron Wickenden

Whether it’s spending time with devil worshipers or the angelic Mr. Rogers, editor Aaron Wickenden always finds a haunting and lovely truth in his work.

We had a chance to speak with editor Aaron Wickenden about the scope of his work, what he finds inspiring, and collaborating with directors.

PremiumBeat: Did Hail Satan? director, Penny Lane, come into the edit bay with a conclusion of any sort? Or did you both find the story as you put together the edit?

Aaron Wickenden: Well, one of the joys of working with Penny is that she is also an incredibly skilled editor. So, when she first contacted me about collaborating on this film, she had a twenty-minute demo that she had cut herself. That piece articulated many of the themes that my co-editor Amy Foote and I would go on to develop in the film. Penny’s demo succeeded in capturing my interest because it didn’t spring forth from conclusions but, instead, posed so many provocative questions, such as What does it mean to call yourself a modern day Satanist? What type of conflicts arise when the Satanic Temple redefines Satanism around tenants that any reasonable person could get behind? Like One should strive to act with compassion and empathy toward all creatures in accordance with reason. And, on an even more basic level What is religion and what is its function?

So, on a hot summer day last year, I joined Penny and her producer Gabriel Sedgwick, at Amy’s Brooklyn edit studio for bagels and our first group mind-meld. They had already begun the editorial process. The challenge was figuring out how to dramatically balance the unfolding of these many questions. As an editor of unscripted films, I’ve discovered — through trial and error — that you never want to be giving the audience answers to questions they don’t have or (god forbid) exposition they don’t need. So, the primary goal is to develop and maintain your audience’s curiosity. That curiosity creates participation and investment. It becomes the engine for your film. Luckily on Hail Satan?, we also had an amazingly straightforward narrative throughline to organize our questions around — which was showing how a few people originally performing a prank became a serious world-wide religious movement.

I left Brooklyn with a heavy hard drive in my luggage and headed back to my home office in Chicago, where I’ve cut the last few films I worked on. So, Amy and I were editing simultaneously using Adobe Premiere Pro. And with some After Effects support, that workflow turned out to be really easy for both of us.

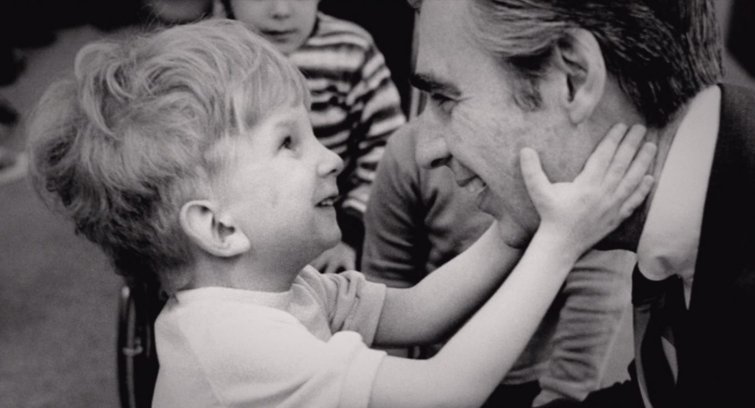

PB: I watched Won’t You Be My Neighbor directly after viewing Leaving Neverland and was so grateful to be in Fred Rogers’s world! There is genuineness in the edit that reflects the subject. Meaning, I never felt manipulated emotionally. Was there a particular scene you felt was the heart of the film and most representative of Fred Rogers?

AW: One of my favorite scenes is the ending of the film, which is actually very different from the ending we had for a long time. When I started on Won’t You Be My Neighbor, my co-editor — the brilliant Jeff Malmberg — had already cut a powerful ending that focused in on the idea of personal responsibility. Our director Morgan Neville was really interested in amplifying the idea that Fred Rogers wasn’t a saint (i.e. a person we could not also be like), and how important and empowering it was to think about the difference we can each make in our communities. As one of our storytellers says, “The question isn’t what would Fred Rogers do? The question is what are you going to do?” That was a profound “walk out idea” for the audience. So we lived with it in the cut for some time, and then set about to work on other parts of the film.

Meanwhile, Morgan had done this beautiful exercise with all of his interviews where he asked people to take a silent, private minute to reflect on someone who had made a profound difference in their lives. It was a mirror of an exercise that Fred would do when he gave speeches on college campuses. So, editorially, we had some very loose sense that this content might get explored earlier in the film. We didn’t really know what that content might become.

It was with that openness to possibility that Morgan asked producer Nicolas Ma and I to watch that footage one day. We screened each moment of reflection in entirety, one after another, which didn’t take very long because each reflection was only a minute long. Nevertheless, for me it was hard not to cry because it was so moving to watch people as they meditate on the idea of love, and recall the people who made the biggest difference in their lives.

At the time, our composer Jonathan Kirkscey had already sent us a few temp music tracks to edit with, and one of them was this evocative and wistful piece called Trolly Music. Using that music as a binding element, we started grouping moments of reflection together in a flow that came together intuitively. First, we see Fred’s collaborators in reflection and watch their faces while hearing Fred lead this exercise himself. The film’s audience is encouraged to participate, as Fred directs us to all think about the people who “Smiled you into smiling, talked you into talking, sung you into singing, loved you into loving.” After a few moments, we hear our storytellers honor the people who made that profound difference in their lives. A storyteller then turns the question back to the director, and asks who he was thinking about? Morgan shares that he was thinking about his own mother. The two of them sit with this and acknowledge each other as having this profound common bond of love. Then, after a moment, we show the people who Fred loved deeply. His two sons and his wife, Joanne Rogers. Joanne ended her reflection saying, “Thank you.”

It was a thank you to Morgan for honoring the legacy of Fred Rogers, it was a thank you for the opportunity to reflect on love, and it was a thank you to the audience of the film for spending some time thinking about the loving energy that flows through everyone and unites all things. It felt like a moment of grace and became the ending of the film.

PB: Generation Wealth is a stunning documentary, unique in that the filmmaker is also a character in the film. The doc explores obsession with wealth and opulence, yet the edit is very down to earth and intimate. The sequence that really struck me was when you linger on a push into the eyes of Suzanne, a hedge fund executive, which was bookended by still shots and a clever use of voiceover. It was very effective. What was the process you and Lauren Greenfield took when working on the film?

AW: Generation Wealth was probably the hardest edit I’ve ever participated in. Lauren and I both like to tell the story about my first day on the job. When I walked into her studio, the wall was lined floor to ceiling with 3×5 cards. Normally, on any other film, those cards would have topics or story beats listed on them (and there would be 1/8th as many). But in this case, the cards simply had names of people that Lauren had interviewed for countless projects over her career. The goal was to weave two and a half decades of work into a single epic narrative. I was gobsmacked, but also thrilled to be working with a master filmmaker who was willing to take a major creative risk entering into uncharted waters.

As a guide for the edit, we had a proof of concept demo in hand that Chad Beck had cut with Lauren, as well as a stellar written treatment that Lauren had developed with Keven McAlester. In both of those pieces, it was established that Lauren would be the primary guide through her corpus. The film would use Lauren’s work and voice to create a cinematic meditation on how the values of the “American Dream” have mutated over time.

Generation Wealth could offer a way to connect the dots, but the challenge of connecting them was like a four dimensional Rubik’s cube. We were repurposing work that had not been designed to fit together, and Lauren’s previous work typically was ethnographic, and thus, did not include her as a character.

Very early on, we started on the adventure of developing Lauren’s voice as a narrator and guide through the conceptual landscape. We had a mic setup in the edit room and once things got cooking, we would be recording VO nearly every day. We were writing and rewriting as we went. This went on for months because the visual materials could be assembled in so many different configurations. So, as an editor, I had to be incredibly agile and develop the skill to both see the infinite possibilities in the material and be ready to completely shift the edit at any moment. That’s really challenging. I remember explaining the process a bit to Breaking Bad editor Skip McDonald at an ACE event. He responded by saying something like, “I have no idea what you’re talking about.”

So, it became clear to me pretty early on that in order to grapple with this type of expansive and generative storytelling experiment — on a reasonable deadline — we needed to bring in more editorial firepower. Michelle Witten (who is an editing genius) joined the team as a co-editor. And then, in the home stretch of the edit, the team expanded to also include Lauren’s frequent collaborators Victor Livingston and Dan Marks. Ultimately, we all worked very hard to hold space for ideas to spark and evolve into sublime moments of connection, like the one you mentioned with Suzanne. As a document, it’s a totally unique time capsule and I’m excited to see what people think of it in 20 years . . . provided we all live that long.

PB: Living with a subject during the length of cutting a documentary must be an emotional journey. What subject of your projects surprised you the most? Which subject moved you the most deeply?

AW: As an editor of unscripted documentary features, I’m drawn to this particular spot in the creative non-fiction landscape because I love witnessing and shaping the stories of people brave enough to make themselves emotionally vulnerable. When you’re working with a director who understands this, then the entire process of editing is one in which we’re very emotionally engaged. For me, that’s a feature of the job and not a flaw. It’s certainly not for everyone, and I know editors who have moved far away from documentary because they crave structure. For me, I’d rather be working with a small band of passionate, brilliant storytellers, who have a great sense humor, and are jumping into the unknown by making a documentary film. I’ve been cutting now for about two decades, so it’s hard to identify what surprised or moved me the most out of all the work. That said, when I’m cutting a difficult scene, and it suddenly starts to unlock itself and go from a pile of fragments to something that almost feels electric in its coherence and completeness — it’s an overwhelming feeling. Sometimes, I have to get up and take a walk in that moment because we’ve just captured lightning in a bottle. I’ve wondered recently if other editors feel this way, too. It might also just be that I’m drinking too much coffee.

PB: We all know documentaries take considerable time to come together. There is numerous footage to view and so many ways the film can be imagined. How do you find your projects? And, given the enormous commitment of time and energy, what factors into your choice to work on a film?

AW: Projects come my way from all sorts of places. Maybe someone will read this article and have the perfect collaboration in mind and drop me a line via my website. Who knows?

The most random way a film came to me was probably Finding Vivian Maier. The producer sent me a private message via Facebook to see if I was interested in talking about the film. The message went into my junk folder, and I didn’t see it for months. When I finally wrote him back, I was surprised they were still looking for an editor. That edit was very homespun, with the core team being just a few people. And ultimately, the film really connected with audiences and went on to be nominated for a BAFTA and Academy Award. So, I try to keep a door open for these types of scrappy projects to still come my way. At the same time, I’ve now built out relationships with many incredible directors who have great projects and the resources to get them made. And I enjoy collaborating when there is support structure in place to allow for our work to be as strong as possible.

What I’m looking for in choosing a film changes a bit from project to project. Right now, I’m cutting a film from my home in Chicago for a director in Australia, and I love that. It means I can spend time around the edges of my day hanging out with my dog. That said, this edit has been a bit isolating, so on my next film, I’m looking to work more directly within a community. At the core, I think I’m always looking to collaborate with directors who have a strong artistic voice and have been drawn to a topic that they are uniquely well-suited to rub up against. In that charged space of friction — between director and subject — I’m looking to help make the sparks fly.

Cover image via Hail Satan? (Magnolia Pictures).

Looking for more industry interviews? Check these out.

- Industry Interview: DJ Stipsen, DP of “What We Do in the Shadows”

- The Sun is Also a Star Film Composer Herdís Stefánsdóttir

- Industry Interview: Miles Hankins — The Composer Behind “Long Shot”

- Industry Interview: CW Costume Designer Catherine Ashton

- Industry Interview: “Whiplash” Production Designer Melanie Jones