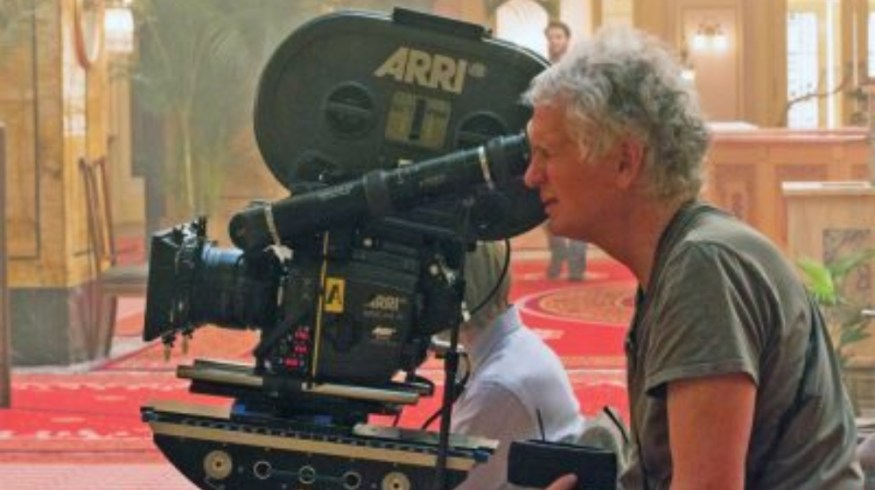

Lighting Comedy and Creating Kitsch with Robert Yeoman

Discover how cinematographer Robert Yeoman keeps his comedies light and helped develop Wes Anderson’s quirky aesthetic.

As anyone who’s ever been a part of a high school film club or stepped foot into a film school classroom will tell you, one of the most distinctive looks in modern film are those from the mind of Wes Anderson. And, while it’s true that Anderson is known to be highly attentive to crafting every element of his films’ visual style, the real man behind the lens for every one of his live-action features (so far) is Robert Yeoman.

However, while Yeoman’s work long ago became intertwined with Anderson’s coffee shop aesthetic, he actually has quite a career as a cinematographer outside of that relationship. His early work garnered him quite a bit of esteem from the Independent Spirit Awards (To Live and Die in L.A., Drugstore Cowboy) and his later works have included several highly successful comedy blockbusters (Yes Man, Bridesmaids).

Let’s take a look at how the man behind such cinematically recognizable films as Rushmore, The Royal Tenenbaums, Life Aquatic, and The Grand Budapest Hotel so successfully elevates arthouse indies and blockbuster comedy franchises alike by combining his craft of kitsch with his artistic and comedic sensibilities.

Finding Your Creative Process

Each person has their own unique voice, and creativity to me is being able to express that voice. I was always inspired by the visual language of films, even more than the writing or anything else. Just images stuck with me and I was so taken by them. So, I started doing cinematography in film school and was good at it, and a natural and had a talent for it. And, I’ve never looked back — I love what I do.

What a fantastic quote by Yeoman to start off our journey in understanding his cinematography. In this intro video by Academy Originals, we get a glimpse into an artist at the highest point of his craft, reflecting back on how he was able to achieve his success. The search for your unique voice and creative process is a fascinating lens to view cinematography as an expression of the language of film. And, that’s exactly what you see throughout Yeoman’s work.

It’s also cool to see some of his early pre-production techniques explained as he talks about traveling to any foreign country that he might be filming in, as well as he and Wes Anderson’s preference for shooting early film photography on set (without lights or actors) to start their own creative processes.

Developing a Visual Grammar

Once we start breaking down the hallmarks of Yeoman’s cinematography, it really comes down to dialing in the visual grammar of the director he’s working with.

For instance, with Wes Anderson in the video above by CookeOpticsTV, Yeoman talks about “finding the center” for every shot as part of his understanding of Anderson’s cinematographic mindset, while working with the messy documentarism of Bill Pohlad’s Love and Mercy, and being open to the improvisation of Paul Feig’s comedies like Bridesmaids and Ghostbusters.

All of the cinematography decisions for each, as Yeoman explains, are part of developing a visual grammar that allows for he and the director to communicate quickly and precisely to best craft the narrative in each and every shot.

Lighting for Clarity and Comedy

Of course, just because Yeoman has a complexity of styles doesn’t mean he isn’t keenly focused on lighting with his own tricks and techniques and creating clear and concise compositions.

In another interview featurette, Yeoman opens up about the challenges of following the sun to use it as one of the greatest light sources for many of his shots — a process he’s perfected by utilizing the app SunSeeker for sun timing and direction.

Also, since Yeoman is most often working with comedies and on more lighthearted features, his focus is often on soft lighting as a means to keep his shots light and clear, as opposed to dark and harsh. His goal for tackling the comic and whimsical is to make his shots look as if they’re as naturally lit as possible in order to best bring the audience into the realness of the story.

Old School Whip Pans and Slow Motion

Moving more specifically into Yeoman’s work with Wes Anderson, there are a couple of looks and techniques that are quickly becoming synonymous with Yeoman’s cinematography. Most notable to many fans of Anderson’s works are the popular whip pans peppered throughout his films and the famous slow-motion shots, which are usually the ending scenes and often the most memorable.

When diving into whip pans, Yeoman takes the old-school approach and, as often as possible, will do them in camera and on set. This requires some complex framing setups with multiple lights and actors ready to go, but it achieves a much more real and imperfect look than when you add the whip pans as a transition in post.

For the slow motion shots, Yeoman confesses that Anderson likes to work as old-school as possible. So, again, he’s often left in simple setups with no more than a dolly and a focus puller to capture these iconic shots in as few takes as possible.

Developing the Wes Anderson Look

When looking back through Yeoman’s career so far, it’s important to recognize that he isn’t simply a means to bringing a director’s vision to screen, but in fact, he’s very much a developer of the looks and aesthetics that we’ve come to know and love.

It would be hard to watch any mainstream comedy these days and not see some of his soft lighting looks in many setups, and it’s even harder to watch any Wes Anderson film — or any Wes Anderson-inspired composition — and not see how much Yeoman has put into developing the overall aesthetic.

Yeoman has given the wide-angle lens a renewed popularity as he’s encouraged Anderson to embrace the odd contours of real life, despite his preference for trying to make everything perfectly symmetric. He’s pushed the limits to what whip pans, crash zooms, and other old-school techniques can actually still capture in camera, and not with simple edits. Ultimately, he’s helped inspire a whole new, younger audience of aspiring cinematographers to embrace kitschy whimsy instead of old, stale compositions and storytelling techniques.

For more cinematographer spotlights and insights, check out these articles below.

- A Look into the Cinematography Stylings of Bradford Young

- The Precise and Expressive Cinematography of Rachel Morrison

- Analyzing the Vast and Versatile Cinematography of Janusz Kamiński

- How Reed Morano’s Cinematography Turns the Camera into a Character

- The Large-Format, Wide-Angle Cinematography of Wally Pfister

Cover image via ASC.