7 Must-Have Books for Every Screenwriter’s Library

There’s no right way or wrong way to write, but there are tools that will set you up for success. Here are seven books every screenwriter needs.

Screenwriters come in all styles—and they all practice the craft differently. The easier your script is to read and understand, the wider the audience with whom it will resonate. That goes for filmmakers and producers, as well as fans and actors.

If you’re interested in writing in the industry, we’ve got seven books you should have on your shelf.

1. The Elements of Style

The cornerstone of any writer’s library must be The Elements of Style (Auroch Press). Whether you’re a screenwriter, an essayist, a novelist, or just an internet ne’er-do-well, the principles of solid, clear, concise writing that appear in the pages of this slender volume are invaluable. This book is so influential that there have been other books written about this book, as well as attacks from linguists claiming it “ate America’s brain.”

Nevertheless, it’s received praise from the likes of Stephen King, Dorothy Parker, and The New York Times. Time Magazine named it one of the 100 most influential books in English since 1923, and it’s sold more than ten million copies.

Originally written by Cornell University English professor William Strunk Jr. in 1918 for use in his classes, the book later caught the attention of E.B. White at The New Yorker. White, who had studied under Strunk, went on to expand The Elements of Style in 1959, thus creating the book’s popular nickname, “Strunk and White.”

So, what does this little firecracker of a book mean for screenwriters? Clarity. While most of the screenplays we write will be necessarily more interesting than the dry examples you’ll find in Strunk and White, the principles of effective writing still apply. You need to be able to write clear, communicable, actionable prose.

If other people lose your themes in bloated exposition and unreadable grammar, then you’re really only writing screenplays for yourself, aren’t you? Master the elegant fundamentals in Strunk and White, and then you can get creative with which rules you break for greater artistic effect.

2. The Timetables of History

You probably haven’t seen this one in many of these books-for-filmmakers roundups. I first discovered this in graduate school, when I was writing papers about medieval literature and needed to provide context and historicity. It wasn’t long, though, before I began using it my novels and my work writing video game scripts. How does it fit into the books-for-screenwriters ecosystem? Worldbuilding.

The Timetables of History is a codex of people, places, and events throughout history. In this post, I talked about the importance of worldbuilding through “meaningful glances.” In short, that means creating the narrative world without lecturing your audience or dragging us through blocks of exposition, both of which can blow the verisimilitude of your story (there you go—cool word for your next dinner party). The best worldbuilding is nuanced, seamless, and subtle.

That’s where the timetables come in. Let’s say your story takes place in the early 1980s—1982, to be precise. Doesn’t matter which genre—noir, horror, tracking down a pirate’s treasure with a gaggle of your best buds before some jerks repossess your houses. You know, all the genres.

If you want to let your audience know when we are and what defines your characters, you can show us with factual glances at things, events, or trends that were going on at the time of your story. The first entry in my copy of the timetables starts at 5,000 BCE. This far back, the entries don’t have a lot of information, but they get more involved as we move forward in time. For example, all I can tell you about the year 5,000 BCE is under “Science, Technology, and Growth”:

The Egyptian calendar, regulated by sun and moon: 360 days, 12 months, 30 days each.

– The Timetables of History

Under “Daily life,” we learn the following:

Earliest cities in Mesopotamia (carbon-test dated).

– The Timetables of History

So, if you were setting your story in 5,000 BCE, you’d have a lot of . . . creative freedom. But back to 1982. What was going on that year that you can include in your story to help with the worldbuilding? 1982 goes on for about four pages in the timetables (we know a lot more about this year than we do 5,000 BCE).

A couple of highlights include “Canada’s Constitution Act comes into force, severing the nation’s last legal ties to the U.K.” (that might be relevant conversation in a diner scene in Vancouver), and “Elizabeth Taylor makes her London theatrical debut in ‘The Little Foxes.'” The list goes on and on, so you can cherry-pick the details that jive best with your story.

(Yes, you could also look up 1982 in Wikipedia, but it’s a deluge of information, and you shouldn’t be on the internet while you’re trying to write anyway.)

3. The Hero with a Thousand Faces

This one you’ve probably heard of. It comes up in every Screenwriting 101 course. This book, the source of Joseph Campbell’s well-known “Hero’s Journey,” famously tracks the original Star Wars trilogy. It’s a handy tool for examining the world’s most compelling and longest-lasting narratives, and determining what makes them tick. This can be enormously beneficial when you’re articulating your story in a script.

In short, the idea of the Hero’s Journey (or “monomyth”) grew out of early psychological and anthropological concepts. Joseph Campbell, channeling Carl Jung’s analytical psychology, compared various religious stories from around the world, and found that the most prominent among them shared remarkably similar narrative steps.

Those steps go a little something like this:

A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.

– The Hero with a Thousand Faces

There are seventeen stages in three different narrative groups in Campbell’s monomyth. You’ll recognize some of them immediately, like “The Call to Adventure,” which you’ve already seen in many of your favorite movies.

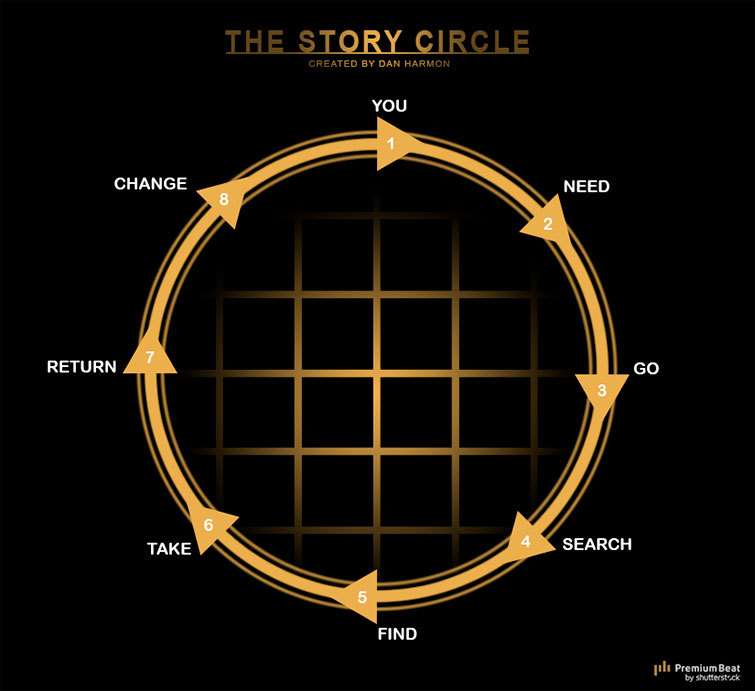

For a more modern take on this kind of folkloric mishmashery, you can also refer to Dan Harmon’s “Story Circle,” which we’ve described for you in detail here.

And, for extra credit, check out Sir James Frazer’s The Golden Bough, a comparative study of mythology and religion—this was a huge influence on Campbell when he was writing The Hero with a Thousand Faces.

4. On Writing

This is Stephen King’s famous memoir on the craft and practice of “writing.” It needs little introduction, since creative writers everywhere are reading, have read, or want to read this book. You might have heard of this one, too.

Less a guide on the nuts and bolts of assembling a story, this memoir is more a meditation on how to do the writing. The ideas here aren’t native to the author’s home horror genre—you can apply them to any kind of creative writing. King’s advocacy for simplicity, for example, supports the idea that “less is more,” when we’re talking about word choice and complexity. For example . . .

Remember that the basic rule of vocabulary is use the first word that comes to your mind, if it is appropriate and colorful.

– On Writing

If you want your script to sound natural, you should use the type of narration and dialog that most closely resembles how real people talk. In general, we don’t speak in complex, florid phrases. We speak to the point, which is King’s . . . uh . . . point. Sometimes, as writers, we get in our own way, and King’s guide helps us see that and get on with the business of telling our stories.

5. The Screenwriter’s Bible

Chances are, you’ve got this on your shelf already. But if you don’t, this is the guide on all spec screenwriting practices. The different people who all work on and with a script during its production are used to encountering the script in familiar ways. This has resulted in a format that makes identifying critical details about a line of text quick and efficient. If you have ambitions of writing in the industry, that means you need to know this format inside and out.

However, the rules you need to format a script, and the practices you need to complete the story and get it down, are many. The Screenwriter’s Bible will march you step-by-step through all the formatting, and you can return to it again and again to look up details you don’t have memorized.

If you don’t deliver scripts in the format that producers are used to seeing, chances are, they’re not going to bother with it. Don’t reject yourself before someone has even read a line of your script. Look up the best practices, and follow them. Once you’ve won every award and re-invented filmmaking, then you can make up your own format.

6. Film Directing: Shot by Shot

This book is the most tangential of the recommendations on this list, but it’s still worth your time. It’s primarily about pre-production—how to visualize the story you need to tell. Aspiring editors, cinematographers, directors, and producers will benefit most directly from the more than 800 photos and illustrations in this seminal work.

However, a screenwriter who speaks Director is a better screenwriter. Other filmmakers are going to take your script and add their contributions to its production. You can help them align their visions to your own if you write a script that respects the work they’ll have to do.

7. The Chicago Manual of Style

You may not often think about “style” when you’re writing your screenplay. After all, if it’s correct English, then what even is a style? In a fascinating turn of events, there’s no single such thing as “correct English.”

Everyone speaks and uses it differently based on where they live and what they’re talking about. Various styles, like Associated Press, Modern Language Association, and American Medical Association, all have different sets of rules for what makes “correct English.” Each of these styles grew out of a different discipline’s need for writing rules, so they don’t all agree. Famously, AP doesn’t call for the oxford comma, yet MLA certainly does.

While you won’t need all the information on citations for your screenplay, the Chicago Manual of Style answers every question you might have about how to punctuate something, how to phrase something, or how to describe things professionally.

AP tends to be a bit squirrelly with its rules and can lead to textual misunderstanding when used in creative writing. MLA is far too formal for professional storytelling, and AMA really should be for the medical industry.

CMS enforces enough rules to keep your writing legible without restricting every creative decision you might make with words and phrases. It’s a highly useful tool that you’ll come back to again and again.

A few more filmmaking articles for your toolkit:

- What “The Invisible Man” Can Teach Aspiring Suspense Filmmakers

- What to Look for in a Dual-Use Photo and Video Digital Camera

- Why Hollywood DP Greig Fraser Is Nearly Right about the New iPhone 13

- 3 Ways Filmmakers Might Actually Use the iPhone 13

- Quick Tips: 5 Rules for Making a Short-Form Documentary

Cover image via Tiko Aramyan.