5 Filmmaking Projects That Can Improve Your Own Work

One of the best ways to get some new filmmaking perspective is to study what others are doing. Here are five examples to get you started.

Industry interviews can be useful for keeping up with production trends and forthcoming projects, but they’re also treasure troves of useful advice that can improve your workflow. We curated five of our favorite interviews to package some filmmaking advice you can use to change you how you see your own projects. From filmmakers shooting new types of horror movies to documentary DPs who capture real life in powerful moving images, here’s what they had to say about their craft.

Daniel Levin, DP of Rest in Power: The Trayvon Martin Story

When you’re trying to document an incredibly important story in recent American history, it takes a keen eye to make sure all of the details are in order. Daniel Levin and his team tirelessly worked to bring this story to the screen in a honest way:

I have been fortunate enough to work with the directors, Jenner Furst and Julia Willoughby Nason, previously, and we had a strong working relationship going into this project. For this series, we wanted to portray the textures and feeling of the real environments that this tragedy and subsequent story took place in. We wanted to feel the atmosphere and nuances of Florida, the Retreat, where the shooting happened, Sanford, Goldsboro, Miami Gardens, America . . . they all had unique aspects, which we wanted to capture for the audience.We also wanted to present the parents of Trayvon Martin, Tracy and Sybrina, in a light that not only showed their strength and courage, but that also reflected the media pressure they have lived with since this tragic event took place — this was part of the reason we captured them on a sound stage, with the footprint of production visible.

Trying to convey a message to the viewer was also one of Levin’s goals; he personally wanted the audience to connect with the film the way he did:

To work on such a socially impactful story was extremely gratifying as well as emotionally intense. To dive deep into the Trayvon Martin story was to not only look into America’s racist past and present, but it also further informed me on the current climate we live in today — something I hope viewers will take away from this series, as well. To me, the beauty of the documentary experience is that as filmmakers and as the audience, we gain a new insight and understanding of stories that can hopefully create a dialogue and an opportunity for change.

You can find the full interview here.

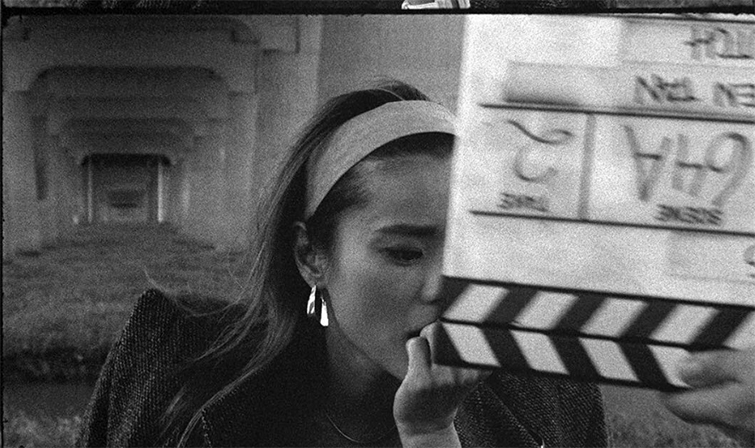

HutcH and the challenges of shooting on film stock

In the current digital age, it seems like a step back for some cinematographers to choose film over digital. For many of those projects that stick with film stock, as the DP for Yen Tan’s 1985 did for HutcH, film lends a certain quality that digital can’t offer:

When we were first starting out on this project, Yen Tan (the director) and I sat down and looked at a lot of different format options. We chose to shoot on Kodak Double X negative film, which is the oldest film stock still made to give our film a timeless aspect. The story and the characters are the most important part, not just the era, so we wanted to put all the focus on that aspect so the audience wouldn’t be distracted by the era.

Why shoot on the oldest film stock available? Because of that warm, fuzzy grain:

We specifically chose the grainiest film stock that we could find. We knew there would be quite a bit of static camera work in the film, which can be difficult for modern audiences to embrace. Having a heavily textured image can subconsciously add motion through the dancing film grain that creeps into even the most static of shots to give viewers something to latch onto.

One giant problem with shooting on film is accessibility — with digital, you can monitor settings and previews through the camera. With film, there are some major challenges to work through:

Most digital cameras today have 14 or more stops of dynamic range. Our film stock, however, had 3 stops — which is similar to an old VHS camcorder from the ’80s. This is what gives the film its stark appearance.

We didn’t really have dailies per se; instead, our scanning process involved sending in our reels to a cinelab in Boston, who used a 4K HDR scanner before sending us back footage in batches for us to review and edit. We’d get footage back about once a week, so instead of having dailies, we had weeklies.

You can find out more about HutcH‘s analog workflow here.

Creating retro ’80s action with filmmaker Benjamin Combes

Why try to create a realistic action movie when an ’80s-styled one just looks like so much more fun? That was Benjamin Combes‘s thought when he decided to create the sythwave-styled Commando Ninja.

To start this project, I went back and re-watched every ’80s action movie I could remember. What stood out was that the action was always very clear and you could always understand what was happening on-screen. Stunt work and choreography was key as the camera was almost always stable on a tripod with minimal dolly movements.

’80s action movies were violent, sexy, and (most of all) fun! Commando, Lethal Weapon, Die Hard, and RoboCop were all ’80s blockbusters that embraced a sense of humor. It’s a great way to defuse all the violence you sometimes witness with funny punchlines and tongue-in-cheek dialogue to help detach and enjoy all the blood and gore.

When recreating ’80s action flicks, the best way to get the look is in production itself. That includes lighting setups, SFX, and shooting styles.

If you want to look like an ’80s movie, the film look is maybe the most important thing. We shot digital on a Panasonic GH4, so we tried to set everything we could to match film quality. Of course that means thinking about lighting, depth of field, focal length, focus, and shooting at 24fps [with] shutter speed [at] 1/48 to get the right motion blur.

When you think of the ’80s, you think of neons and pastel colors like pink. Action movies from the ’80s were no different, and we worked hard to bring retro lighting setups to life. Of course, we didn’t want to abuse it, but we tried to bring back some nostalgia with colored gels for dark and night scenes and bright neons when we could.

For me, real squibs is a huge detail that always stood out to me from the classic ’80s movies. We were able to hire some professional stuntmen who could handle things like squibs, grenade explosions, and swordfights. We also made an effort to use awful-looking dummies and fake body parts as they would in the ’80s for any stunts where people are exploded or thrown from balconies. Likewise, real locations [and] practical SFX were also the best part of the shooting days, and actors loved that. I remember actor Philippe Allier was particularly excited to be chased by a full-scale velociraptor.

To find out more about Combes’s workflow for creating retro action, read the full interview here.

Shooting in remote locations with The Ritual DP Andrew Shulkind

How do you get a full crew and a giant load of gear deep into the woods? Lots and lots of planning, including the use of Google maps, according to the DP of Netflix’s The Ritual, Andrew Shulkind:

First of all, it was a UK production, and so there was a different kind of health and safety department that is committed to this kind of production. We are on steep mountainsides. The grips rigged a pulley system with a motor and a wench that was taking gear up the steep hill.

Another thing was, of course, as you are scouting, you’re preparing people for the level of challenge they are going to have to endure. For example, This is going to be an insane cable run, or How can we land the generator easier? We are looking at Google maps to find other roads that might be nearby. We relied heavily on balloons. We also built some custom LEDs that we can use with battery power and not have to run some insane cables to get some good depth in the background.

A DP’s camera choice can often define a movie’s feel. Here’s why Shulkind went with the Canon C-series C300 and C700:

So, the C700 wasn’t available when we first started. We then had a pre-production model, a kind of prototype model that had a bunch of these Japanese characters on the outside. Even if I had access to that camera from the beginning, I wouldn’t have used it for everything we did because we were running around — we did a bunch of Steadicam and other lightweight gimbal work. That was where the C300 really killed it. I had done a movie with that camera prior, and the C200 too, and just knew what we could get out of it. I knew what was possible in terms of low light. The Alexa was something that we used all the time.

Based on his experience in the industry, this is his advice to new filmmakers:

I think our business is growing in a different direction. There is a big opportunity for up-and-comers like there may never have been before. Now we are kind of entering a new space which includes interactivity, and it includes mobile-first activity. The fact is that movies are not the gold standard that everyone thought they were 65-70 years ago. So, I think in terms of getting out there, getting your work seen, you have to be able to really hone your craft.

You can check out the rest of his interview here.

Making a documentary cinematic with The Trade cinematographer Matt Porwol

Episodic documentaries have become a staple of streaming platforms such as Netflix and HBO. On Showtime, viewers are exploring the opioid epidemic through the The Trade, with cinematographer Matt Porwoll shooting some of its pivotal moments. When shooting documentaries, reducing the crew’s footprint is an important part of the process for Matt:

One thing that we very purposefully did on this film was we tried to limit our footprint as much as possible. It made everybody a lot more comfortable because we only had two people in the field per team. I had a producer, and it was just the two of us for the entire time. So through that consistency, where we weren’t changing out crew members every trip, we weren’t adding people, removing people. And so, I think through that there was a level of just comfort that we established pretty early on. Much of being a documentarian doesn’t really have a lot to do with the camera — it just has to do with how you present yourself and how you explain why you’re there and how you approach these difficult and delicate situations in a respectful way. We are people behind the camera, and we care for you, and we understand everything that you’re going through, and we just want to understand it more and share that with the audience. I think that motivated a lot of people. Especially with the families that we filmed.

Shooting documentary-style also means that you’ve got to be prepared for any type of lighting conditions — and be ready to go at a moment’s notice for shooting:

One thing that we really wanted to do was, again, in minimizing the footprint, to come up with style guides for the show. We focused on almost building a set of limitations to work within. Instead of bringing a bunch of gear and having every focal length and the perfect camera, we kind of focused on reining it all in and saying we’re only going to really have with us what we can carry without having to go back to the car. On all these storylines, you have to be flexible — you have to be ready to go. And so, we shot on the Canon C300 Mark II, which I’ve been working with since the day it came out. It’s really solidified itself as the perfect documentary camera: it’s small, it’s lightweight, it has incredible image quality, and it’s just flexible and ergonomic for documentary use. It doesn’t ever fight you — the last thing you want in a camera is having to spend time thinking about where a button is, how to access something, or having complicated menus.

You can find out more about shooting episodic documentaries here.

Cover image via Daniel Levin.

Looking for more industry interviews? Check these out.

- Interview: Outspoken Comedian Tess Rafferty on Getting Political

- Interview: Composer Federico Jusid Makes Some Noise in Hollywood

- Interview: Tips for Crowdfunding Over $100,000 for Your Documentary Projects

- Interview: Tracy Andreen on the Romance of Writing for Hallmark

- Screenwriter James V. Hart on Career, Coppola, and Creating a Method